| |

The XII Corps played a decisive role in the defense of the Union right wing, on Culp's Hill, at Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863. Yet, the officers and men of the XII Corps received no Medals of Honor. We are beginning a research process to recommend several officers and enlisted men of the XII Corps for our nation's highest honor.

The report, "Retroactive Civil War Medals of Honor for the XII Corps," was written by William T. Endicott, whose ancestor fought in the XII Corps on Culp's Hill at Gettysburg.

It was prepared specifically for this website.

The report, "African-Americans Awarded WWII MOHS Retroactively," was also prepared by William T. Endicott. |

RETROACTIVE CIVIL WAR MEDALS OF HONOR FOR THE XII CORPS

William T. Endicott

3-16-14

This document looks at the question of obtaining a Congressional Medal of Honor (MOH) today for action in the Civil War, particularly at Culp’s Hill in the Battle of Gettysburg. I’d like to thank John Heiser, U.S. National Park Service historian at Gettysburg, who read the original manuscript and suggested a number of changes that have improved it.

The document is organized in 7 parts:

1. Background. The MOH has experienced some controversy recently for several reasons. First, is the allegation that the standards have been unrealistically high today, and second because the Army apparently “lost” the application of Captain William D. Swenson in order to punish him for speaking against the Army. Lastly, 24 MOHs are about to be awarded to men from past wars who are judged to have been overlooked due to discrimination.

2. Information on MOHs awarded for Gettysburg. Of the 63 MOHs awarded for service at Gettysburg, not a one was for the defense of Culp’s Hill, even though it was vital for the Union victory at the battle of Gettysburg.

3. Changing criteria for receiving a Civil War MOH. During the Civil War, the criteria for receiving an MOH were much less stringent than they are today. And even though one retroactive MOH was recently awarded for Civil War action under Civil War criteria, it appears that an even more recent one was awarded only under today’s much tougher criteria, which is presumably what any future retroactive MOHs would have to be awarded under.

4. Four cases of recent MOH applications for Civil War service. By studying the cases of Andrew Jackson Smith, who was awarded a Civil War MOH in 2001, and Alonzo Cushing, who seems poised to get one as of this writing for service at the battle of Gettysburg, we can learn lessons about the obstacles that have to be overcome. So can we learn from the unsuccessful cases of Philip G. Shadrach and George D. Wilson. The biggest obstacles are a) getting Congress to waive the statute of limitations for applying for the award and b) is getting the Secretary of Defense to approve the award. A congressional office needs to submit a request to DoD for these purposes and the ensuing process can be very lengthy and very political.

5. Six Medal Of Honor candidates for the defense of Culp’s Hill, July 1-3, 1863. So far, the following have been identified as men for whom a possible case can be made for a retroactive MOH:

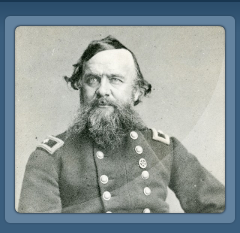

- Brigadier General George S. Greene, Commander of the Third Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Corps;

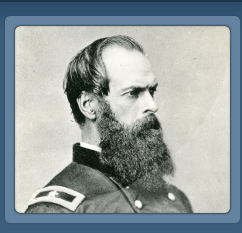

- Colonel David Ireland, Commanding Officer, 137th New York, Third Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Corps;

- Lieut. Colonel Charles R. Mudge, 2nd Massachusetts, Third Brigade, First Division, Twelfth Corps;

- Captain Joseph H. Gregg, 137th New York;

- Major Joshua G. Palmer, 66th Ohio, First Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Corps;

- Color Sergeant William C. Lilly, 149th New York, Third Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Corps.

We will be adding some officers and enlisted men of the Twelfth Corps who are deserving of recognition for their heroic efforts in the defense of Culp’s Hill but do not necessarily meet the criteria to receive the Medal of Honor. Among these officers and men whom re recommend for special mention are Lieut. Colonel Ario Pardee, Jr., Commanding Officer, 147th Pennsylvania, First Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Corps, and Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger, Commander, Third Brigade, First Division, Twelfth Corps.

There were regiments from two other corps that supplied reinforcements to the Twelfth Corps in the defense of Culp’s Hill. We will include recommendations for mention of officers and men from these reinforcing units.

One individual of note is Lieut. Colonel Rufus Dawes, 6th Wisconsin Regiment of the Iron Brigade.

6. After action reports for Culp’s Hill. In the report of General Greene, there are comments that support an MOH for Colonel Ireland. In the report of Colonel Ireland, there are comments that support an MOH for Captain Gregg.

7. Review of all citations for Gettysburg MOH recipients. A review of all 63 citations for MOHs awarded for Gettysburg shows that capturing a flag was the most common way to the get the MOH at Gettysburg, just as it was in the Civil War generally, with leading a “storming party” and rescuing a comrade, the next most frequent ways.

Return to Top of Page

1. BACKGROUND. The MOH has been in the news in recent years for a several reasons, but at this point it’s not known how sensitivities over this might impact a request for a Civil War MOH. First, U.S Rep. Duncan Hunter (R-Cal), an Iraq Marine veteran and member of the House Armed Services Committee, wrote a letter to then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta complaining that Medals of Honor were being denied today in cases where they appear to be well-deserved and that the process of approving awards was taking too long. Initially, DoD said that the nature of the warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan made it harder to find cases that met the established criteria for the MOH. But since then, there have been more awards of the MOH, thus seeming to vindicate Hunter’s claim.

The second reason the MOH has been in the news is the case of Army Captain William Swenson. First of all, it has come out that his application for an MOH was inexplicably expunged from computer files and thus “lost” for 19 months (until a duplicate file was found), allegedly in order to punish Swenson for publically criticizing higher ranking Army officers for failing to take appropriate action in the fight he was involved in, thus causing unnecessary U.S. casualties. Indeed, two officers were reprimanded for this, and the Army admitted that it made mistakes in the case and would take corrective action to improve the process. Secondly, there has been an allegation that the case of a Marine involved in the same action, Dakota Meyer, was exaggerated and embellished by the Marines who had not had anyone receive the MOH in 38 years in order to speed its way through the approval process.

The third reason the MOH is in the news today is because as of this writing, 24 Army men from WWII, Korea, and Vietnam who had been discriminated against because of ethnicity are about to receive the MOH retroactively (and 21 of them posthumously).

Return to Top of Page

2. INFORMATION ON MOHS AWARDED FOR GETTYSBURG SERVICE

* The MOH was created in 1863, only 4 months before the Battle of Gettysburg. Thus, it was not as widely known then as it is today.

* 63 men received the MOH for actions at Gettysburg, but not one of them after having been killed in the battle. This is the case for most Civil War recipients. For some reason, unlike today, it appears that it helped a lot to be alive while the medal was being pursued on your behalf.

* Furthermore, not a single MOH was awarded for action at Culp’s Hill, yet according to John Heiser, U.S. National Park Service historian at Gettysburg, the defense of Culp’s Hill was as vital to Union victory as was the defense of Little Round Top for which Joshua Chamberlain most famously got the MOH, or repelling Picket’s Charge, for which the most Gettysburg MOHs were awarded.

* Only 19 of the Gettysburg MOHs (30%) were issued during the war itself, with all the rest of them being awarded in later years. In fact, 36 of them (57%), including the one for Joshua Chamberlain, were issued between 1890 and 1900. In other words, a long delay in awarding Civil War MOHs has always been the norm.

* 30 (48%) were awarded for picking up a flag or carrying a flag, or capturing a flag. (Andrew Jackson Smith who got his MOH in 2001 got it for this, which would not qualify under today’s more stringent criteria.)

* 16 were awarded to officers (25%), and only two of them to generals.

* Major General Dan Sickles was awarded the MOH for encouraging his and other troops as he was carried on a stretcher to the rear while wounded. His citation reads: “Displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.” But what is not recorded in the citation is that Sickles put his corps in a dangerous position and then scrambled to save it while under attack. As one officer put it, Sickles was lucky to have been wounded or he would have faced a court martial.

* Brigadier General Alexander Webb is the other general to receive the MOH and his citation reads: “Distinguished personal gallantry in leading his men forward at a critical period in the contest.” Again, the citation does not do justice to the act, only in Webb’s case, what he did was even more heroic than the citation indicates. He personally rallied one regiment (71st Pennsylvania), attempted to lead one of his regiments (72nd Pennsylvania) in a counter-charge, then raced between the opposing lines to help rally another (69th Pennsylvania) in fear of losing their hold on the stone wall near the Angle. All of this involved the retaking of Cushing’s battery and the Union position at the Angle, which Webb was responsible for.

* MOH recipient Colonel Joshua Chamberlain’s case is similar to candidate Colonel David Ireland’s case. Chamberlain’s citation reads: “Daring heroism and great tenacity in holding his position on the Little Round Top against repeated assaults, and carrying the advance position on the Great Round Top.”

* On the surface MOH recipient Colonel Wheelock G. Veazey’s case might sound like Colonel David Ireland’s case. Veazey’s citation reads: “Rapidly assembled his regiment and charged the enemy's flank; charged front under heavy fire, and charged and destroyed a Confederate brigade, all this with new troops in their first battle.” But the difference is that whereas Veazey demonstrated exemplary personal leadership in front of an inexperienced regiment, and while exposed to enemy fire, Ireland’s command had enough experience to not require him to act in the fashion Veazey did.

* MOH recipient Major Edmund Rice’s case sounds like candidate Captain Joseph H. Gregg’s case, except Gregg was killed and Rice was not. Rice’s citation reads: “Conspicuous bravery on the third day of the battle on the countercharge against Pickett's division where he fell severely wounded within the enemy's lines.”

* MOH recipient Captain William E. Miller’s case sounds like candidate Captain Joseph H. Gregg’s case, too, again except that Gregg was killed. Miller’s citation reads: “Without orders, led a charge of his squadron upon the flank of the enemy, checked his attack, and cut off and dispersed the rear of his column.”

Return to Top of Page

3. CHANGING CRITERIA FOR RECEIVING A CIVIL WAR MOH.

A total of 1,522 MOHs were awarded for Civil War Service, 1,198 of them for Army service.

During the Civil War, the MOH was not only the highest medal for valor, it was the only medal for valor. Consequently, it was often awarded for actions that would not qualify by today’s standards. (There were, however, other ways of honoring heroic actions that do not exist today, such as giving a man a higher “brevet rank,” in other words, a rank that existed in title only, but did not entail the pay or pension rights of the higher rank).

Furthermore, the application process was much less formal than today. Basically, you wrote the Secretary of War asking for the MOH, maybe submitting letters from witnesses to buttress your claim and maybe not.

Initially, the MOH was viewed with a certain amount of skepticism because it smacked of European practices that Americans were trying to get away from. In later years, however, when recipients noticed that they gained a certain amount of prestige in their communities for winning the MOH and were asked to lead parades and such, more and more men applied for it.

This accelerated until it reached the point where more than 700 men applied for it retroactively between 1890 and 1900 alone and 683 got it – an acceptance rate of more than 90%.

This caused President McKinley in 1897 to direct the Army to establish tighter policies regarding the application and award procedures. These were tightened still further in 1917, when 911 people, or about a third of those awarded up to that time, were “purged” from the official list. After that, today’s much more stringent requirements were more or less in place.

The result is seen in the statistics. Of all the 3,473 MOHs ever awarded, 1,522 or 44 % were awarded for Civil War service, even though many more soldiers have served in all the wars since then. For example, about 16 million men served in WWII alone, about 5 times as many as served in the Union army, but only 462 MOHs were awarded for WWII. So, it’s obvious that since WWI, it has been much harder to get the MOH.

Return to Top of Page

4. FOUR CASES OF RECENT MOH APPLICATONS FOR CIVIL WAR SERVICE.

There have been four cases in the last 13 years, one involving Andrew Jackson Smith, who actually got the MOH in 2001, two involving Philip D. Shadrach and George D. Wilson who did not get it in 2008, and a fourth involving Alonzo Cushing who seems poised to get it as of this writing.

What follows is a review of these cases, including in some instances interviews with people who worked on them and who speak about the obstacles that have to be overcome in order to get the MOH retroactively for a Civil War veteran.

ANDREW JACKSON SMITH (1843-1932). A runaway slave, he served with the Massachusetts 55th Regiment, and received an MOH in 2001 (the same time Teddy Roosevelt got his retroactively for San Juan Hill). At the battle of Honey Hill, Smith picked up not one, but two flags, after the color bearers had been shot and carried the flags through the rest of the battle. This was the most typical situation a man could get the MOH for in the Civil War.

Dr. Burt G. Wilder who had been the regimental surgeon for the 55th Massachusetts, began a lifelong correspondence with Smith in hopes of securing a MOH for him. Smith was finally nominated for the MOH in 1916, but the Army denied him, erroneously citing a lack of official records documenting the case. One story at time was that Smith's regimental commander, Colonel Alfred Hartwell, was severely wounded and carried from the battle early in the fighting. Thus, the story goes, he was forced to complete his after action report at home while recuperating from his wounds and didn’t know about Smith’s action. As we’ll see in a minute, though, Hartwell did write about it, but it took years to find what he wrote.

It has also been alleged that another problem was that in 1916 when the request for a MOH for Smith occurred it was a time of increasing racial prejudice. And just a short while later African-Americans were denied the right to serve as combat troops in the American army in World War I (although some -- the 92nd and 93d Division -- did serve in combat while attached to the French army).

Nevertheless, Smith’s two daughters, Caruth Smith Washington and Susan Smith Shelton, both now deceased, preserved some original documents pertaining to Smith’s life and military service.

Then, more recently, Andrew Bowman of Indianapolis, Indiana, Smith’s grandson, was determined that his grandfather should receive the Medal of Honor, and he spent several years collecting records, conducting research and working with government officials and a history professor at Illinois State University. Bowman wrote an account of “Andy” Smith’s life at http://www.coax.net/people/lwf/AJSMITH.HTM.

Finally, new records pertaining to Smith's service were found in the National Archives, where they had been since the end of the Civil War. One of these new documents, one written by the commanding officer, Colonel Alfred Hartwell, was quoted at the 2001 MOH award ceremony:

"The leading brigade had been driven back when I was ordered in with mine. I was hit first in the hand just before making a charge. Then my horse was killed under me and I was hit afterward several times. One of my aides was killed and another was blown from his horse. During the furious fight, the color-bearer was shot and killed and it was Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith who would retrieve and save both the state and federal flags."

Here, at long last, was undeniable proof of what Smith had done.

In order to get a retroactive MOH, among other things, Congress has to pass legislation waiving the time limit for applying. And in Smith’s case, Senator Dick Durbin (D-Ill) and former Rep. Thomas Ewing (R-Ill) were the ones who shepherded such a measure through Congress and President Clinton signed it into law.

Dr. Sharon MacDonald, then an Illinois State University professor (now retired), and Robert “Rob” Beckman, a Dunlap, Illinois high school history teacher were the ones who found Smith's service records in the National Archives and Colonel Hartwell’s report about Smith’s actions, and they pursued the case with Durbin and Ewing.

On January 16, 2001, 137 years after the Battle of Honey Hill, Smith got the medal. President Bill Clinton presented it to several of Smith's descendants during a ceremony at the White House.

The following is Smith’s MOH citation:

"The President of the United States of America, authorized by an act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded in the name of the Congress the Medal of Honor to Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith, United States Army, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.

"Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith of Clinton, Illinois, as a member of the 55th Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry, distinguished himself on 30 November, 1864, by saving his regimental colors after the color- bearer was killed during a bloody charge in the battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina. In the late afternoon, as the 55th Regiment pursued enemy skirmishers and conducted a running fight, they ran into a swampy area backed by a rise where the Confederate army waited. The surrounding woods and thick underbrush impeded infantry movement and artillery support. The 55th and 54th Regiments formed columns to advance on the enemy position in a flanking movement.

"As the Confederates repelled other units, the 55th and 54th Regiments continued to move into flanking positions. Forced into a narrow gorge crossing a swamp in the face of the enemy position, the 55th color sergeant was killed by an exploding shell and Corporal Smith took the regimental colors from his hand and carried them through heavy grape and canister fire.

"Although half of the officers and a third of the enlisted men engaged in the fight were killed or wounded, Corporal Smith continued to expose himself to enemy fire by carrying the colors throughout the battle. Through his actions, the regimental colors of the 55th Infantry Regiment were not lost to the enemy.

"Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith's extraordinary valor in the face of deadly enemy fire is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon him, the 55th Regiment, and the United States Army."

In speaking of the circumstances about Smith getting his medal, Rob Beckman has said:

"I will warn you that the process is a lot more political than most people imagine. Even with the strong case that we presented and the clear evidence of racial discrimination involved, we still had to move several times to break our case free from politically motivated hold ups."

It is not known, however, what evidence Beckman has for making these charges.

PHILIP G. SHADRACH AND GEORGE D. WILSON. These two Privates were part of “Andrew’s Raiders,” the 24 Union men who participated in the “Great Locomotive Chase” that occurred on April 12, 1862, and for which the first MOHs ever created were awarded. Of the 24 men involved, two were civilians and thus were not eligible for the MOH. Of the remaining 22, all received the MOH, except Shadrach and Wilson, who were among the 8 men the Confederates hanged as spies. 4 men received the MOH posthumously after being hanged and it’s unclear why Shadrach and Wilson were not added to that list. Some reports said that Shadrach was disqualified because he had enlisted under a false name.

Former Rep David L. Hobson (R-Ohio) introduced a bill to award these two the MOH but it did not succeed. Hobson is now the president of Vorys Advisors LLC an affiliate of the law firm Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease, and he resides in Springfield, Ohio.

Why the two did not get the MOH seems odd especially in view of this report of the Judge Advocate General wrote about the incident to the Secretary of War, which included the following:

Among those who thus perished was Private Geo. D. Wilson, Company C, 21st Ohio Volunteers. He was a mechanic from Cincinnati, who, in the exercise of his trade, had travelled much through the States North and South, and who had a greatness of soul which sympathized intensely with our struggle for national life, and was in that dark hour filled with joyous convictions of our final triumph. Though surrounded by a scowling crowd, impatient for his sacrifice, he did not hesitate, while standing under the gallows, to make them a brief address. He told them that, though they were all wrong, he had no hostile feelings toward the Southern people, believing that not they but their leaders were responsible for the Rebellion; that he was no spy, as charged, but a soldier regularly detailed for military duty; that he did not regret to die for his country, but only regretted the manner of his death; and he added, for their admonition, that they would yet see the time when the old Union would be restored, and when its flag would wave over them again. And with these words the brave man died. He, like his comrades, calmly met the ignominious doom of a felon—but, happily, ignominious for him and for them only so far as the martyrdom of the patriot and the hero can be degraded by the hands of ruffians and traitors.

ALONZO CUSHING of Wisconsin. Cushing died at his artillery post helping to stop Picket’s Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg. He commanded Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery. Ironically, the First Sergeant who served with Cushing at the time, Frederick Fuger, was awarded MOH for the same action.

A number of internet sites and even at least one book claim that Cushing has already been awarded the MOH, but that is not true. It’s true that the Secretary of the Army approved the award in 2010 and even that the House of Representatives approved it the first time in 2012. But then the measure died in the Senate and the process had to start over again. It passed the House again in 2013 and this time it even passed the Senate. Now the only remaining obstacle is to have Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel sign off on it, which he is expected to do.

The Alonzo Cushing case is different from the Andrew Jackson Smith case in a few interesting ways. First of all, Cushing was killed at Gettysburg, so he wasn’t around to push for the MOH himself. Most men who got the MOH for Civil War service were alive when they got it (although some from the “Great Locomotive Train Chase were not). Secondly, Cushing was never married, so there weren’t descendants to push for him to get the MOH, either. And lastly, many people not related to Cushing have worked on this case for many years.

Margaret Zerwekh, now in her 90s, who lives on the Delafield, Wisconsin property once owned by Cushing's family, first started working the case by writing Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire in 1987. Her grandfather was a Civil War veteran, which was part of the reason she was interested. But according to online stories, all Proxmire did was insert material into the Congressional Record about the matter; he didn’t formally ask Congress to waive the statute of limitations for applying for the award, nor did he ask the Army to approve the award.

Zerwekh subsequently wrote letters to presidents, senators and congressmen, and was herself written up in the New York Times for her efforts.

Another thing that helped Cushing’s case was the fact that Kent Masterson Brown, a Kentucky lawyer, published a biography of Cushing in 1993 called “Cushing of Gettysburg: The Story of a Union Artillery Commander.”

Finally, in 2003, then-Senator Russell D. Feingold (D-Wisconsin), officially nominated Cushing for the MOH and was even successful in getting the Secretary of the Army, John McHugh, to approve it in 2010. But also in 2010, Feingold lost his re-election bid, so he couldn’t continue working on the case. But Senators Herb Kohl (D-Wisconsin) and Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin) the man who had defeated Feingold, took up the case.

In 2012, the U.S. House passed a measure authorizing the MOH for Cushing, but it was blocked in the Senate by Senator Webb (D-Virginia), who said at the time: “ It is impossible for Congress to go back to events 150 years ago to make individual determination in a consistent, equitable and well-informed manner.”

Subsequently, U.S. Representatives Ron Kind, (D-Wisconsin) and Jim Sensenbrenner (R- Wisconsin), pushed waiving the statue of limitations in the House and they succeeded in getting the House to pass it as an amendment to the FY 2014 Defense Authorization bill on June 14, 2013. The Senate passed the bill, with the amendment intact, on December 20, 2013.

A staff member from Rep. Kline’s office explained that when Senator Webb blocked the Cushing provision, he requested that DoD write a report about how Medals of Honor retroactive to the Civil War are awarded. (His request for it was formally included in the Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4310, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013. House Report 112-705, page 765). A copy of the report is in the appendix to this section.

Although the report is helpful in describing process, when it refers to criteria for determining eligibility for receiving Civil War MOHs retroactively it unfortunately does not explicitly state what those criteria are.

There is still one more step before Alonzo Cushing can receive his medal: Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel needs to sign off on it. After the Secretary of the Army signed off on it in 2010, then-Defense Secretary Leon Panetta signed off on it, too. But DoD is saying that now that Panetta’s gone and Hagel’s in, Panetta’s approval is not enough and Hagel needs to approve it, too It is expected that Hagel will sign off, however, although when is not certain.

Close observers to the case say, however, that one problem with the Cushing MOH is who it should be given to, with the normal requirement being that it should be given to a blood relative and so far, none has been identified.

Senator Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin) and Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-Wisconsin, (202 224 5653) led the effort on the Senate side.

APPENDIX -- REPORT TO THE COMMITTEES ON ARMED SERVICES OF THE SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

ON

PROCESSES AND MATERIALS USED BY REVIEW BOARDS FOR CONSIDERATION OF MEDAL OF HONOR RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTS OF HEROISM THAT OCCURRED DURING THE CIVIL WAR

June 2013

Prepared By:

Office of the Under Secretary of Defense

Personnel and Readiness

Executive Summary

The Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) does not have any standing review boards for considering Medal of Honor (MOH) recommendations endorsed by a Military Department Secretary to the Secretary of Defense (SecDef). Each recommendation is reviewed based on its own merit against MOH award criteria at the time the action occurred to determine if there is proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the member performed the valorous action for which they were recommended. Each MOH recommendation is staffed by the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness for consideration by the SecDef. Prior to consideration by the SecDef, each MOH recommendation is forwarded to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for endorsement and is reviewed by the Department of Defense (DoD) General Counsel for legal sufficiency.

The Military Department Secretaries have well-established procedures for processing MOH recommendations, including those from the Civil War era, within their respective Military Departments. The processes and materials used by senior decorations and awards boards vary slightly by Military Department. The senior decorations and awards review boards serve in an advisory capacity to the Military Department Secretary, who is solely responsible for determining whether a MOH recommendation merits personal endorsement to the SecDef. Civil War era MOH recommendations are, and should be, rare. Prior to notification of a favorable determination of such a MOH recommendation pursuant to section 1130 of title 10, U.S. Code, great care is taken to ensure the recommendation is fully vetted in accordance with the procedures outlined in the body of this report.

The DoD submits this report on processes and materials used by review boards for consideration of MOH recommendations for acts of heroism that occurred during the Civil War to respond to the report request contained in Conference Report to Accompany H.R. 4310, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (House Report 112-705, page 765). Specifically, the conferees “direct the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the service secretaries, to report to the Committees on Armed Services of the Senate and the House of Representatives, not later than 90 days after enactment of this Act, on the process and materials used by review boards for consideration of Medal of Honor recommendations for acts of heroism that occurred during the Civil War.”

Office of the Secretary of Defense

OSD does not have any standing review boards for considering MOH recommendations endorsed by a Military Department Secretary to the SecDef. Each recommendation is reviewed based on its own merit against MOH award criteria at the time the action occurred to determine if there is proof beyond a reasonable doubt that the member performed the valorous action for which they were recommended. Each MOH recommendation is staffed by the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness for consideration by the SecDef. Prior to consideration by the SecDef, each MOH recommendation is forwarded to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for endorsement and is reviewed by the DoD General Counsel for legal sufficiency.

The Military Department Secretaries are responsible for establishing procedures for processing MOH recommendations within their respective Military Departments in accordance with OSD guidance contained in DoD Manual 1348.33, Volume 1, “Manual of Military Decorations and Awards: General Information, Medal of Honor, and Defense/Joint Decorations and Awards.” Each Military Department’s established procedures include a review by a senior decorations and awards board. The processes and materials used by the boards vary slightly by Military Department. However, it is important to note that each senior review board merely serves in an advisory capacity to the Military Department Secretary, who is solely responsible for determining whether or not to endorse a MOH recommendation to the SecDef. The Department of the Air Force did not exist during the Civil War. Accordingly, this report focuses on processes and materials used by the Department of the Army and the Department of the Navy (Navy and Marine Corps) review boards.

Department of the Army: Processes and Materials used by Review Boards to Consider of MOH recommendations for Civil War Acts of Heroism.

MOH recommendations for actions performed by Union Soldiers during the Civil War have traditionally been initiated by a Member of Congress pursuant to section 1130, title 10, U.S. Code, “Consideration of proposals for decorations not previously submitted in timely fashion: procedures for review.”

The Army Decorations and Awards Branch, Army Human Resources Command (HRC), Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel (G-1), reviews each MOH request submitted pursuant to section 1130, ensuring compliance with governing DoD and Army directives. This includes ensuring the recommendation contains a signed MOH recommendation, eyewitness accounts, and other documents supporting the recommendation. For Civil War MOH recommendations, justification for award often includes salient documents from the National Archives and Records Administration, letters and personnel records from the Adjutant General Office, Historical Society information (for example, articles, journals, and historical markers), and other documents deemed pertinent to the recommendation. Only verifiable facts and documents from reliable sources are used to make determinations regarding MOH recommendations from the Civil War era.

Each MOH recommendation is then forwarded to the Commander (CDR), HRC, through the Army Decorations Board (ADB). It is important to note that the ADB is advisory in nature and has no authority to approve or disapprove an award. Army Decorations and Awards Branch and advises the CDR, HRC, accordingly. The CDR, HRC, reviews each MOH recommendation against MOH award criteria, taking into consideration the advice of the ADB. The CDR, HRC, based on authority delegated by the Secretary of the Army regarding MOH recommendations that are unfavorably reviewed by the ADB, may: 1) disapprove the MOH recommendation; 2) approve award of a lower-level decoration; or 3) forward the MOH recommendation to the Secretary of the Army. The CDR, HRC, must forward all recommendations favorably reviewed by the ADB to the Secretary of the Army for consideration.

Each section 1130 MOH recommendation, prior to being forwarded to the Secretary of the Army, is reviewed by the Army Center for Military History to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of supporting documents. Subsequent to the historical review, the MOH is forwarded to the Secretary of the Army through the Senior Army Decorations Board (SADB).

It is important to note that the SADB is advisory in nature and has no authority to approve or disapprove an award. The SADB reviews the MOH recommendation against MOH award criteria and advises the Secretary of the Army accordingly. Upon review by the SADB, the MOH recommendation is forwarded to the Army Judge Advocate General, the Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel (G-1), the Chief of Staff of the Army, and the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, each of whom also advises the Secretary of the Army regarding the merit of the recommendation.

All MOH recommendations under section 1130 endorsed by the Secretary of the Army to the SecDef have been fully vetted and evaluated in accordance with the procedures outlined above.

Department of the Navy (Navy and Marine Corps): Processes and Materials used by Review Boards to Consider MOH recommendations for Civil War Acts of Heroism.

The Department of the Navy has not processed a MOH recommendation for acts of heroism performed during the Civil War for many years. The last Department of the Navy MOH awarded for actions during the Civil War was approved more than 96 years ago.

Department of the Navy awards for combat heroism must be based on the testimony of eyewitnesses. The current requirement is for at least two signed and notarized eyewitness statements attesting to the individual’s heroic act(s). Additionally, all award recommendations must either be initiated by the commanding officer of the recommended individual or routed via the individual’s commanding officer for endorsement. There are no standing waivers for any of these requirements; they apply regardless of the conflict or time period during which the act took place.

From the foregoing, it is apparent that as a practical matter it would be nearly impossible to meet the basic requirements for recommending a Civil War Navy MOH. However, in an exceptional case where evidence was discovered of a MOH recommendation previously initiated by the commanding officer of a sailor/marine, that recommendation would be processed in the same manner as all other MOH recommendations for previous conflicts.

A MOH recommendation for a previous conflict is first reviewed by the awards branch of either the Navy Staff (sailors) or Headquarters, U. S. Marine Corps (marines). The awards branch staff will ensure the recommendation package is complete and complies with policies and regulations. Of particular concern is that it include a summary of action describing the valorous act(s) in detail, a proposed award citation, at least two notarized eyewitness statements attesting to the valorous act, and only such additional documents or material (for example, action reports, final investigation reports, deck logs, and medical documentation), that provide factual evidence of the individual’s heroic act(s).

If the recommendation meets regulatory requirements, it is reviewed by either the Chief of Naval Operations’ awards board, or the Headquarters Marine Corps awards board, as applicable. These boards are advisory in nature and do not have authority to approve or disapprove an award. The award is then endorsed by the applicable Service Chief: Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC) for marines; Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) or Director, Navy Staff (DNS) for sailors. The Service Chief may recommend the MOH, approve a lesser award, or disapprove the award.

After endorsement by the CNO or CMC, all MOH recommendations are reviewed by the Navy Department Board of Decorations and Medals (NDBDM), which advises the Secretary of the Navy on awards matters. The NDBDM will recommend to the Secretary of the Navy that he either: a) favorably endorse the MOH and forward the case to the President via the SecDef; b) approve a lesser award in lieu of the MOH; or c) disapprove the recommendation outright (for example, no award will be made). Although only the President has the authority to approve award of the MOH, the Secretary of the Navy is delegated authority to disapprove a recommendation for the MOH (or award a lesser decoration). No one else within the Department of the Navy is currently delegated MOH disapproval authority, and therefore, once properly originated, all MOH recommendations are forwarded to the Secretary of the Navy for a personal decision.

Summary

The Military Departments and OSD have well-established processes and procedures in place for reviewing MOH recommendations, including those from the Civil War era. Civil War era MOH recommendations are, and should be, rare. Prior to notification of a favorable determination of such a MOH recommendation pursuant to section 1130 of title 10, U.S. Code, great care is taken to ensure the recommendation is fully vetted in accordance with the procedures outlined in this report.

INTERPRETATION OF WHAT THE ABOVE SAYS

Based on the above report, the following appear to be the steps necessary to get the Secretary of Defense to approve the awarding of a Civil War MOH:

* A Member of Congress sends an application to the Army “pursuant to section 1130, title 10, U.S. Code, ‘Consideration of proposals for decorations not previously submitted in timely fashion: procedures for review.’“

* The case gets referred to the Army’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel in the Decorations and Awards Branch of the Army’s Human Resources Command.

* This office reviews the MOH request ensuring compliance with governing DoD and Army directives. This includes ensuring the request contains:

- A signed MOH recommendation.

- Eyewitness accounts.

- Other documents supporting the recommendation.

- Often salient documents are also included, such as from the National Archives and Records Administration, letters and personnel records from the Adjutant General’s Office, Historical Society information (for example, articles, journals, and historical markers), and other documents deemed pertinent to the recommendation are also consulted. Only verifiable facts and documents from reliable sources are considered.

* If the request makes it through all of the above, the Army

Decorations and Awards Branch sends it to the Commander of the Army Human Resources Command.

* The Commander of the Human Resources Command reviews the request against MOH award criteria [that I'm trying to get a copy of] taking into consideration the advice of the Army Decorations and Awards Branch.

* The request is also sent to the Army Center for Military History to ensure the accuracy and authenticity of supporting documents.

* After the historical review, the Commander of the Human Resources Command can 1) disapprove the request; 2) recommend a lesser award; or 3) recommend the award of an MOH to the Secretary of the Army. If he wants to recommend it to the Secretary of the Army, he sends the MOH request to Secretary of the Army’s Senior Army Decorations Board. If the recommendation from the Army Decorations and Awards Branch is favorable, the Commander must forward the request to the Secretary of the Army, he has no choice. But if it is unfavorable, he has the discretion to send it to the Secretary of the Army anyway.

* The case is then referred to the Secretary of the Army’s Senior Army Decorations Board. This board then reviews the case against MOH award criteria.

* After that, the MOH recommendation is forwarded to 4 places:

- The Army Judge Advocate General

- The Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel

- The Chief of Staff of the Army

- The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs

Each of these places also advises the Secretary of the Army regarding the merits of the recommendation.

* If all of this comes out positive, the Secretary of the Army approves the request and sends it to the Secretary of Defense.

Return to Top of Page

5. SIX MEDAL OF HONOR CANDIDATES FOR CULP’S HILL ACTION

* Brigadier General Greene. According to U.S. Park Service historian at Gettysburg, John Heiser, “General Greene is one of the unsung heroes of Culp’s Hill.” He did get some recognition, being the only XII Corps Brigade Commander to get a statue at Gettysburg, but he is largely forgotten in the public’s memory today.

When General Meade ordered General Slocum to send men from Culp’s Hill to Little Round Top, Slocum reluctantly obeyed but got permission to leave General Greene at Culp’s Hill with one brigade -- 5 regiments with a total of 1,424 men.

When Greene first arrived at Culp's Hill early on the morning of July 2, he immediately realized his position demanded breastworks. Disregarding the objections of his division commander, Brigadier General John Geary, Greene ordered construction to begin.

Greene estimated that he never had more than 1,300 troops at any one time to face 4,000 -- 5,000 Confederates. He maintained his defense of the hill by using his limited resources wisely, rotating troops to and from the battle line to restock their cartridge boxes and clean their weapons. The eager Union troops cheered on their comrades as they raced back and forth, pushing each other to greater and greater heights of fervor and determination. Greene rode up and down the line to motivate them, showing no regard for his personal welfare.

Greene estimated Confederate losses at 2,400, which included several officers and 130 prisoners. By contrast, the 3d Brigade's losses amounted to 307 killed, wounded, and missing.

(Source: Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, pp. 295-297. Greene, George S., Brevet-Major-General, United States Volunteers, “The breastworks at Culp’s Hill, II.” In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 3, Century Magazine, 1887, p. 317. New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefields of Gettysburg and Chattanooga, In Memorium, George Sears Greene, Albany: J. B. Lyon Company, 1909.)

* Colonel Charles R. Mudge of the Massachusetts 2nd Volunteer Infantry. On July 3, the third day of the battle of Gettysburg, his regiment made an attack against the Confederate troops at the base of Culp's Hill, near Spangler’s Spring. He replied to the order to attack, "Well it is murder, but it's the order." Early in the charge a bullet struck Mudge just below the throat and killed him instantly. His regiment suffered 137 casualties in the assault. (Source: Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, pp. 232-233, 341, 348, 350. Mores, Charles F., History of the Second Massachusetts Regiment of Infantry; Gettysburg: A Paper Read at the Officers Reunion in Boston, May 10, 1878, Boston: George H. Ellis Printer, 1882.)

* Lieut. Colonel David Ireland of the 137th New York Volunteer Infantry (456 men). He made some crucial decisions in replacing his troops to beat back Confederates attempting to flank his position on Culp’s Hill, thus helping to “save the day.” But Ireland died of dysentery in 1864, so he wasn’t around to push for an MOH. (Source: "137th Regiment Infantry, Historical Sketch by Surgeon John Farrington," From New York at Gettysburg. Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, pp. 220, 221, 300, 302. Cleutz, David, Fields of Fame & Glory: Col. David Ireland and the 137th New York Volunteers, 2010.)

* Captain Joseph H. Gregg 137th New York Volunteer Infantry. He was killed while leading a squad in a bayonet charge on Culp’s Hill against Confederate soldiers threatening to turn the flank of the Union line. Modern accounts differ as to whether Gregg made the charge on his own impulse or was ordered to, and whether it succeeded in driving the Confederates back or not. But John Heiser, the U.S. National Park Service historian at Gettysburg, says he believes sources show that Gregg did indeed execute the charge on his own impulse and that it did indeed turn back Confederate forces. “Understanding the immediate threat to his regiment’s position on the hill, he ordered and led a bayonet charge against a force threatening his right and rear, successfully thwarting the southern probe, although it cost Gregg his life.”

Colonel Ireland reported what Gregg had done (see quotes below).

Joseph Gregg enlisted in the New York 137th Volunteers in 1862 and achieved the rank of captain. On July 2 at Gettysburg, when a Confederate attack struck his position, Gregg led a bayonet charge and was wounded in the left shoulder and chest. The arm was amputated and Gregg died in the hospital on July 3. Colonel Ireland reported "Captain Gregg with a small squad of men charged with the bayonet the enemy that were harassing us most, and fell mortally wounded, while leading and cheering on his men” (citation OR Vol 27, Pt 1, p 867) And later: “Captain Gregg fell, nobly leading on his men.” (Source: "137th Regiment Infantry, Historical Sketch by Surgeon John Farrington," From New York at Gettysburg, pp. 942-43. Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, p. 221. Cleutz, David, Fields of Fame & Glory: Col. David Ireland and the 137th New York Volunteers, 2010.)

* Major Joshua G. Palmer, 66th Ohio. He was mortally wounded while cheering on his men as they swept around the front of the Federal earthworks, engaging Confederate sharpshooters and skirmishers on the hillside and at the base of the hill. Veterans of the 66th Ohio placed a marker to mark where he fell. So far, however, the only report that has been identified testifying to what he did is that of Lt. Colonel Eugene Powell of the 66th Ohio, who says: “It becomes my painful duty to report to you that Maj. J. G. Palmer fell, mortally wounded, while cheering on his men in our advance across the intrenchments.” (Source: Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, p. 296. Baumgartner, Richard A., Buckeye Blood: Ohio at Gettysburg. Blue Acorn Press, 2003.)

* Color Sergeant William C. Lilly, 149th New York. Color Sergeant William C. Lilly carried the regimental colors of the 149th New York Infantry. Lilly carried the regimental standard during the battle of Culp’s Hill. After the battle, they counted 80 Confederate bullet holes in the flag. The flagstaff was hit and broken twice. Sergeant Lilly spliced the staff together and returned it to its position. Sergeant Lilly was wounded while saving the colors. (Source: Pfanz, Harry W., Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993, p. 302.)

Return to Top of Page

6. AFTER ACTION REPORTS ABOUT CULP’S HILL

UNION AFTER ACTION REPORTS ABOUT CULP’S HILL

* Report of General Greene of July 12, 1863. “The officers and men behaved admirably during the whole of the contest. Colonel Ireland was attacked on his flank and rear. He changed his position and maintained his ground with skill and gallantry, his regiment suffering very severely. Where all so well did their duty it is difficult to specially commend any individual, but all have my hearty commendation for their gallant conduct and for the good service rendered their country.”

* Report of Colonel David Ireland July 6, 1863. “Early on the morning of Thursday, July 2, we marched from the position on the left to a position on the right of the road to Gettysburg and parallel to it. In this position we constructed a line of breastworks covering the front of the regiment. The breastworks were completed about noon. We marched in them and remained there until about 6 p. m., when I received orders to send out a company of skirmishers. Company H, Capt. C. F. Baragar, was detailed. At the same time we were ordered to change our position to the line of works constructed by General Kane's brigade, to occupy which we had to form line one man deep. In this position the right of our regiment was entirely unprotected.

About 7 p. m. our skirmishers were driven in by the enemy, who were advancing in force, and, as near as I could see, in three lines.? We remained in this position fighting the enemy until about 7.30 o'clock, when the enemy advanced on our right flank. At this time I ordered Company A, the right-flank company, to form at right angles with the breastworks, and check the advance of the enemy, and they did for some time, but, being sorely pressed, they fell back a short distance to a better position, and there remained until Lieutenant Cantine, of General Greene's staff, brought up a regiment of the First Corps. I placed them in the position occupied by Company A, but they remained there but a short time. They fell back to the line of works constructed by the Third Brigade. At this time we were being fired on heavily from three sides--from the front of the works, from the night, and from a stone wall m our rear. Here we lost severely in killed and wounded.

At this time I ordered the regiment back to the line of works of the Third Brigade, and formed line on the prolongation of the works, and there held the enemy in check until relieved by the Fourteenth New York Volunteers, Colonel Fowler commanding, and the Second Brigade, Second Division, General Kane commanding.

While in this position, and previous to being relieved, Captain Gregg, in command of a small squad of men, charged with the bayonet the enemy that were harassing us most, and fell; mortally wounded, leading and cheering on his men.

When relieved by the Fourteenth New York, we formed line in their rear, and in that position remained during the night.

At 3 a. m. of Friday, July 3, we relieved the One hundred and forty-seventh New York Volunteers in the breastworks, and at 4 a. m. the enemy advanced with a yell and opened on us. Their fire was returned, and kept up unceasingly until 5.45 o'clock, when we were relieved in splendid style by the Twenty-ninth Ohio Volunteers, commanded by Captain Hayes.

We relieved them at 7 a. m., and were relieved again at 9. 30 a. m. We relieved the Twenty-ninth Ohio again about 10.15 a. m. We were there but a short time when the fire slackened, and we retired a short distance, when the men rested and cleaned their arms.

We relieved the Fifth Ohio Volunteers, Colonel Patrick commanding, at 9 p. m., and were relieved by him at 1 a. m. on Saturday, July 4. We were not under fire again during the engagement.

During the heavy musketry firing on the morning of Friday, July 3, a squad of 52 rebels surrendered to Capt. Silas Pierson, who sent them to the rear. From them we learned that we had been engaged with the Stonewall Division, of Ewell's corps.

Throughout the whole of the engagement the officers and men of this regiment did their duty, and did it well-more especially those officers that are killed. Captain Gregg fell, nobly leading on his men. I had thanked Captain Williams for his coolness and courage but a short time before he fell, and Lieutenant Van Emburgh, acting adjutant, was everywhere conspicuous for his bravery, and fell, cheering the men. He was a good and brave officer. His loss will be much regretted. Lieutenant Hallett fell, doing his duty. From our heavy loss in killed and wounded, some idea may be formed of the severity of the fire we were under. We had killed, wounded, and missing as follows: Killed, 38, and wounded, 86.*

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

DAVID IRELAND

Colonel, Commanding 137th New York Volunteers.

CONFEDERATE AFTER ACTION REPORTS ABOUT CULP’S HILL

* Report of General Robert E. Lee, July 4, 1863: “On the 2d July, Longstreet’s corps with the exception of one division, having arrived, we attempted to dislodge the enemy, and, though we gained some ground, we were unable to get possession of his position. The next day, the third division of General Longstreet having come up, a more extensive attack was made. The works on the enemy’s extreme right and left were taken, but his numbers were so great and his position so commanding, that our troops were compelled to relinquish their advance and retire. It is believed that the enemy suffered severely in these operations, but our own loss has not been light.”

* Report of General Robert E. Lee, July 7, 1863: “Finding the position too strong to be carried, and, being much hindered in collecting necessary supplies for the army… I determined to withdraw to the west side of the mountains.

* Report of General Robert E. Lee, July 31, 1863: “A full account of these engagements cannot be given until the reports of the several commanding officers shall have been received, and I shall only offer a general description. General Ewell attacked directly the high ground on the enemy's right, which had already been partially fortified.

…Ewell also carried some of the strong positions which he assailed, and the result was such as to lead to the belief that he would ultimately be able to dislodge the enemy. The battle ceased at dark.

…the battle recommenced in the afternoon of the 3d, and raged with great violence until sunset. Our troops succeeded in entering the advanced works of the enemy, and getting possession of some of his batteries, but our artillery having nearly expended its ammunition, the attacking columns became exposed to the heavy fire of the numerous batteries near the summit of the ridge, and, after a most determined and gallant struggle, were compelled to relinquish their advantage, and fall back to their original positions with severe loss.

* Report of Lt. General Richard S. Ewell: “Immediately after the artillery firing ceased, which was just before sundown, General Johnson ordered forward his division to attack the wooded hill in his front, and about dusk the attack was made. The enemy were found strongly intrenched on the side of a very steep mountain, beyond a creek with steep banks, only passable here and there.

… Steuart, on the left, took part of the enemy's breastworks, and held them till ordered out at noon next day.

… Just before the time fixed for General Johnson to advance, the enemy attacked him, to regain the works captured by Steuart the evening before. they were repulsed with very heavy loss, and he attacked in turn, pushing the enemy almost to the top of the mountain, where the precipitous nature of the hill and an abatis of logs and stones, with a very heavy work on the crest of the hill, stopped his farther advance.

* From the report of Colonel H.A. Barnum, commander of the New York 149th, written by Captain C.P. Horton: “When so many did so well, it would be invidious to make special mention of some in the rank and line who were particularly brave and meritorious. I should disappoint my entire command, however, if I did not call especial attention to the consummate skill and unsurpassed coolness and bravery of Lieut. Col. Charles B. Randall, who was dangerously wounded in the left breast and arm while cheering the men to their work.”

Return to Top of Page

7. REVIEW OF ALL CITATIONS FOR GETTYSBURG MOH RECIPIENTS. What follows is a list of all 63 Gettysburg Medal of Honor citations in order to better understand the reasons Gettysburg veterans were awarded the medal.

REASON MEDAL OF HONOR WAS AWARDED

They break down into the following categories in order of frequency, which roughly mirrors what happened in the Civil War generally:

Capturing a flag or securing a Union flag: 29

Leading a charge: 11

Rescuing a comrade: 5

Capturing guns or holding onto guns: 5

Conspicuous gallantry 5

Other: 8

TOTAL 63

YEAR WHEN MOH AWARDED

Most Gettysburg MOHs were awarded decades after the event:

1864-1865: 20 (all for capturing a flag)

1866-1869: 3

1887-1905: 40

TOTAL 63

PLACE FOR WHICH MOH WAS AWARDED

(NB. Not all places have been accounted for)

The place for which the most Gettysburg MOHs were awarded was Pickett’s Charge, with 12 out of 63 or 19%:

Defense against Picket’s Charge:

19th Massachusetts

(De Castro; Falls; Jellison; Rice; Robinson) 5

14th Connecticut

(Bacon; Flynn; Hinks) 3

126th New York

(Brown; Dore; Wall) 3

4th U.S. Artillery

(Fuger) 1

71st Pennsylvania

(Clopp) 1

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Defense of Little Round Top:

Charge on Devil’s Den: 6

(Furman; Hart; Johnson; Mears; Roush;

Smith of 6th Pa)

(NB John Heiser says the term “Devil’s Den”

is a misnomer because in actuality, these

medals were given for the capture of a log house

that was a ½ mile away from the Devil’s Den.)

20th Maine: 2

(Chamberlain, Tozier)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bliss Farm:

1st Delaware

(McCarren; Mayberry; Postles) 3

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Wheatfield/Peach Orchard:

140th Pennsylvania

(Pipes; Purman) 2

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

July 1, 1863

150th Pennsylvania

Reisinger

Huidekopper 2

TOTAL 29

LIST OF GETTYSBURG MOH RECIPIENTS:

Nathaniel M. Allen; Corporal, Company B, 1st Massachusetts Infantry. Issued March 29, 1899.

July 2nd. When his regiment was falling back, this soldier, bearing the national color, returned in the face of the enemy's fire, pulled the regimental flag from under the body of its bearer, who had fallen, saved the flag from capture, and brought both colors off the field.

Elijah W. Bacon; Private, Company F, 14th Connecticut Infantry. issued December 1, 1, 1864

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 16th North Carolina regiment (C.S.A.).

George G. Benedict; Second Lieutenant Company C, 12th Vermont Infantry. Issued June 27, 1892.

July 3rd. Passed through a murderous fire of grape and canister in delivering orders and re-formed the crowded lines.?Benedict was detached from his regiment, which was not on the battlefield, as Aide de Camp to General Stannard.

Morris Brown, Jr.; Captain, Company A, 126th New York Infantry. Issued March 6,1869.

July 3rd. Capture of flag.

Hugh Carey; Sergeant, Company E, 82d New York Infantry. Issued February 6, 1888

July 2nd. [Other sources say July 3] Captured the flag of the 7th Virginia Infantry (C.S.A.), being twice wounded in the effort.

Casper R. Carlisle; Private, Company F, Independent Pennsylvania Light Artillery. Issued December 21, 1892.

July 2nd. Saved a gun of his battery under heavy musketry fire, most of the horses being killed and the drivers wounded.

Joshua L. Chamberlain; Colonel, 20th Maine Infantry. Issued August 11, 1893.

July 2nd. Daring heroism and great tenacity in holding his position on the Little Round Top against repeated assaults, and carrying the advance position on the Great Round Top.

Harrison Clark; Corporal, Company E, 125th New York Infantry. Issued June 11, 1895

July 2nd. Seized the colors and advanced with them after the color bearer had been shot.

John E. Clopp; Private, Company F, 71st Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued February 2, 1865.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 9th Virginia Infantry (C.S.A.), wresting it from the color bearer.

Jefferson Coates; Sergeant, Company H, 7th Wisconsin Infantry. Issued June 29 1866.

July 1st. Boscobel, Wis. Grant County, Wis. For unsurpassed courage in battle, where he had both eyes shot out.

Joseph H. De Castro; Corporal, Company I, 19th Massachusetts Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 19th Virginia regiment (C.S.A.).

George H. Dore; Sergeant, Company D, 126th New York Infantry. Issued December 1,1864.

July 3rd. The colors being struck down by a shell as the enemy were charging, this soldier rushed out and seized the flag, exposing himself to the fire of both sides.

Richard Enderlin; Musician, Company B, 73d Ohio Infantry. Issued September 11, 1897.

July 1st and 2nd. Voluntarily took a rifle and served as a soldier in the ranks during the first and second days of the battle. Voluntarily and at his own imminent peril went into the enemy's lines at night and, under a sharp fire, rescued a wounded comrade.

Benjamin F. Falls; Color Sergeant, Company A, 19th Massachusetts Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864

July 3rd. Capture of flag.

John B. Fassett; Captain, Company F, 23d Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued December 29, 1894.

July 2nd. While acting as an aide, voluntarily led a regiment to the relief of a battery and recaptured its guns from the enemy.

Christoher Flynn; Corporal, Company K, 14th Connecticut Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 52d North Carolina Infantry (C.S.A.).

Frederick Fuger; Sergeant, Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery. Issued August 24, 1897

July 3rd. All the officers of his battery having been killed or wounded and five of its guns disabled in Pickett's assault, he succeeded to the command and fought the remaining gun with most distinguished gallantry until the battery was ordered withdrawn.

Chester S. Furman; Corporal, Company A, 6th Pennsylvania Reserves. Issued August 3, 1897.

July 2nd. Was 1 of 6 volunteers who charged upon a log house near Devil's Den, where a squad of the enemy's sharpshooters were sheltered, and compelled their surrender.

Edward L. Gilligan; First Sergeant, Company E, 88th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued April 30, 1892.

1 July 1863. Assisted in the capture of a Confederate flag by knocking down the color sergeant.

John W. Hart; Sergeant, Company D, 6th Pennsylvania Reserves. Issued August 3, 1897.

July 2nd. Was one of six volunteers who charged upon a log house near the Devil's Den, where a squad of the enemy's sharpshooters were sheltered, and compelled their surrender.

William B. Hincks; Sergeant Major, 14th Connecticut Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. During the high water mark of Pickett's Charge on July 3rd. the colors of the 14th Tennessee Infantry C.S.A. were planted 50 yards in front of the center of Sgt. Maj. Hincks' regiment. There were no Confederates standing near it but several were lying down around it. Upon a call for volunteers by Major Ellis to capture this flag, this soldier and two others leaped the wall. One companion was instantly shot. Sgt. Maj. Hincks outran his remaining companion running straight and swift for the colors amid a storm of shot. Swinging his saber over the prostrate Confederates and uttering a terrific yell, he seized the flag and hastily returned to his lines. The 14th Tennessee carried twelve battle honors on its flag. The devotion to duty shown by Sgt. Maj. Hincks gave encouragement to many of his comrades at a crucial moment of the battle.

Thomas Horan; Sergeant, Company E, 72d New York Infantry. Issued April 5, 1898.

July 2nd. In a charge of his regiment this soldier captured the regimental flag of the 8th Florlda Infantry (C.S.A.).

Henry S. Huidekoper; Lieutenant Colonel, 150th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued 27 May 1905.

1 July 1863. While engaged in repelling an attack of the enemy, received a severe wound of the right arm, but instead of retiring remained at the front in command of the regiment.

Francis Irsch; Captain, Company D, 45th New York Infantry. Issued May 27, 1892.

July 1st. Gallantry in flanking the enemy and capturing a number of prisoners and in holding a part of the town against heavy odds while the Army was rallying on Cemetery Hill.

Benjamin H. Jellison; Sergeant, Company C, 19th Massachusetts Infantry.

July 3rd.. Newburyport, Mass. Newburyport, Mass. Issued December 1, 1864. Capture of flag of 57th Virginia Infantry (C.S.A.). He also assisted in taking prisoners.

Wallace W. Johnson; Sergeant, Company G, 6th Pennsylvania Reserves. Issued 8 August 1900.

July 2nd. With five other volunteers gallantly charged on a number of the enemy's sharpshooters concealed in a log house, captured them, and brought them into the Union lines.

Edward M. Knox; Second Lieutenant, 15th New York Battery. Issued October 18, 1892.

July 2nd. Held his ground with the battery after the other batteries had fallen back until compelled to draw his piece off by hand; he was severely wounded.

John Lonergan; Captain, Company A, 13th Vermont Infantry. Issued 28 October 1893.

July 2nd. Gallantry in the recapture of 4 guns and the capture of 2 additional guns from the enemy; also the capture of a number of prisoners.

John B. Mayberry; Private, Company F, 1st Delaware Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag.

Bernard McCarren; Private, Company C, 1st Delaware Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag.

George W. Mears; Sergeant, Company A, 6th Pennsylvania Reserves. Issued February 16, 1897.

July 2nd. With five volunteers he gallantly charged on a number of the enemy's sharpshooters concealed in a log house, captured them, and brought them into the Union lines.

John Miller; Corporal, Company G, 8th Ohio Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of 2 flags.

William E. Miller; Captain, Company H, 3d Pennsylvania Cavalry. Issued July 21, 1897.

July 3rd. Without orders, led a charge of his squadron upon the flank of the enemy, checked his attack, and cut off and dispersed the rear of his column.

Harvey M. Munsell; Sergeant, Company A, 99th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued 5 February 1866.

1-July 3rd. Gallant and courageous conduct as color bearer. (This noncommissioned officer carried the colors of his regiment through 13 engagements.)

Henry D. O'Brien; Corporal, Company E, 1st Minnesota Infantry. Issued 9 April 1890.

July 3rd. Taking up the colors where they had fallen, he rushed ahead of his regiment, close to the muzzles of the enemy's guns, and engaged in the desperate struggle in which the enemy was defeated, and though severely wounded, he held the colors until wounded a second time.

James Pipes; Captain, Company A, 140th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued 5 April 1898.

2 July 1863 at Gettysburg and August 25, 1864 at Reams Station, Va. While a sergeant and retiring with his company before the rapid advance of the enemy at Gettysburg, he and a companion stopped and carried to a place of safety a wounded and helpless comrade; in this act both he and his companion were severely wounded. A year later, at Reams Station, Va., while commanding a skirmish line, voluntarily assisted in checking a flank movement of the enemy, and while so doing was severely wounded, suffering the loss of an arm.

George C. Platt; Private, Company H, 6th United States Cavalry. Issued July, 12, 1895.

At Fairfield, Pa. July 3rd. Seized the regimental flag upon the death of the standard bearer in a hand-to-hand fight and prevented it from falling into the hands of the enemy.

James Parke Postles; Captain, Company A, 1st Delaware Infantry. Issued July 22, 1892.

July 2nd. Voluntarily delivered an order in the face of heavy fire of the enemy. (A 600 yard ride carrying orders under intense fire)

James L. Purman; Lieutenant, Company A, 140th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued October 30, 1896.

July 2nd. Voluntarily assisted a wounded comrade to a place of apparent safety while the enemy were in close proximity; he received the fire of the enemy and a wound which resulted in the amputation of his left leg.

William H. Raymond; Corporal, Company A, 108th New York Infantry. Issued March 10, 1896

July 3rd. Voluntarily and under a severe fire brought a box of ammunition to his comrades on the skirmish line.

Charles W. Reed; Bugler, 9th Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery. Issued August 16, 1895.

July 2nd. Rescued his wounded captain from between the lines.

J. Monroe Reisinger; Corporal, Company H, 150th Pennsylvania Infantry. Awarded January 25, 1907.

July 1st. Specially brave and meritorious conduct in the face of the enemy.

Edmund Rice; Major, 19th Massachusetts Infantry. Issued 6 October 1891.

July 3rd.Conspicuous bravery on the third day of the battle on the countercharge against Pickett's division where he fell severely wounded within the enemy's lines.

James Richmond; Private, Company F, 8th Ohio Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag.

John H. Robinson; Private, Company I, 19th Massachusetts Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 57th Virginia Infantry (C.S.A.).

Oliver P. Rood; Private, Company B, 20th Indiana Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 21st North Carolina Infantry (C.S.A.).

George W. Roosevelt; First Sergeant, Company K. 26th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued July 2, 1887.

At Bull Run, Va., 30 August 1862. At Gettysburg, Pa., July 2nd. At Bull Run, Va., recaptured the colors, which had been seized by the enemy. At Gettysburg, he captured a Confederate color bearer and colors, in which effort he was severely wounded.

J. Levi Roush; Corporal, Company D, 6th Pennsylvania Reserves. Issued August 3, 1897.

July 2nd. Was 1 of 6 volunteers who charged upon a log house near the Devil's Den, where a squad of the enemy's sharpshooters were sheltered, and compelled their surrender.

James M. Rutter; Sergeant, Company C, 143d Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued October 30 1896.

July 1st. At great risk of his life went to the assistance of a wounded comrade, and while under fire removed him to a place of safety.

Martin Schwenk; Private, Company B, 6th United States Cavalry. Issued 23 April 1889.

July 3rd. At Fairfield, Pa. For bravery displayed on the field of battle in an attempt to carry a communication through the enemy's lines, and for the rescue of a wounded officer of the 6th United States Cavalry from the hands of the enemy.

Alfred J. Sellers; Major, 90th Pennsylvania Infantry. Issued July 21, 1894.

July 1st. Voluntarily led the regiment under a withering fire to a position from which the enemy was repulsed.

Marshall Sherman; Private, Company C, 1st Minnesota Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 28th Virginia Infantry (C.S.A.).

Daniel E. Sickles; Major General, U.S. Volunteers. Issued October 30, 1897.

July 2nd. Displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.

Thaddeus S. Smith; Corporal, Company E, 6th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry. Issued May 5, 1900.

July 2nd. Was 1 of 6 volunteers who charged upon a log house near the Devil's Den, where a squad of the enemy's sharpshooters were sheltered, and compelled their surrender.

Charles Stacey; Private, Company D, 55th Ohio Infantry. Issued June 23, 1896

July 2nd. Voluntarily took an advanced position on the skirmish line for the purpose of ascertaining the location of Confederate sharpshooters, and under heavy fire held the position thus taken until the company of which he was a member went back to the main line.

James B. Thompson; Sergeant, Company G, 1st Pennsylvania Rifles. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of 15th Georgia Infantry (C.S.A.).

Andrew Tozier; Sergeant, Company I, 20th Maine Infantry. Issued August 13, 1898.

July 2nd. At the crisis of the engagement this soldier, a color bearer, stood alone in an advanced position, the regiment having been borne back, and defended his colors with musket and ammunition picked up at his feet.

Wheelock G. Veazey; Colonel, 16th Vermont Infantry. Issued September 8, 1891.

July 3rd. Rapidly assembled his regiment and charged the enemy's flank; changed front under heavy fire, and charged and destroyed a Confederate brigade, all this with new troops in their first battle.

Jerry Wall; Private, Company B, 126th New York Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag.

Francis A. Waller; Corporal, Company I, 6th Wisconsin Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 1st. Capture of flag of 2d Mississippi Infantry (C.S.A.).

Alexander S. Webb; Brigadier General, U.S. Volunteers. Issued September 28, 1891.

July 3rd. Distinguished personal gallantry in leading his men forward at a critical period in the contest.

William Wells; Major, 1st Vermont Cavalry. Issued September 8, 1891.

July 3rd. Led the second battalion of his regiment in a daring charge.

James Wiley; Sergeant, Company B, 59th New York Infantry. Issued December 1, 1864.

July 3rd. Capture of flag of a Georgia regiment.

Return to Top of Page

|

AFRICAN-AMERICANS AWARDED WWII MOHS RETROACTIVELY

by

William T. Endicott

February 23, 2014

In 1993, during the Clinton Administration, the Army contracted Shaw University, a historically black University in Raleigh, North Carolina, to do a study of why no African-American soldier received the Medal of Honor (MOH) in WWII although 1.2 African-Americans had served in the war, many of them in combat.

The 272-page study by the Shaw team, entitled "The Exclusion of Black Soldiers from the Medal of Honor in World War II,” concluded that racial discrimination had contributed to the military's overlooking the contributions of black soldiers and recommended the Army consider 10 African American soldiers for the MOH, most of whom had received lesser medals.

While the study found no “explicit written evidence in official documents” proving that African-Americans were the targets of discrimination in the awarding the MOH, the study did find that there were informal, unwritten policies that prevented any African-American from being awarded the MOH.

The Army agreed that 7 of the 10 soldiers recommended by the Shaw study should receive the MOH. In October, 1996 Congress passed the necessary legislation waiving the statue of limitations for applying for the medals, thus allowing the President to award them. The medals were presented by President Clinton in a white House ceremony on January 13, 1997. Vernon Baker was the only recipient still living and present to receive his MOH the other six soldiers received theirs posthumously, with their medals being presented to family members.

Here are the citations for each man:

First Lieutenant Vernon J. Baker

Citation: For extraordinary heroism in action on 5 and 6 April 1945, near Viareggio, Italy. Then Second Lieutenant Baker demonstrated outstanding courage and leadership in destroying enemy installations, personnel and equipment during his company's attack against a strongly entrenched enemy in mountainous terrain. When his company was stopped by the concentration of fire from several machine gun emplacements, he crawled to one position and destroyed it, killing three Germans. Continuing forward, he attacked an enemy observation post and killed two occupants. With the aid of one of his men, Lieutenant Baker attacked two more machine gun nests, killing or wounding the four enemy soldiers occupying these positions. He then covered the evacuation of the wounded personnel of his company by occupying an exposed position and drawing the enemy's fire. On the following night Lieutenant Baker voluntarily led a battalion advance through enemy mine fields and heavy fire toward the division objective. Second Lieutenant Baker's fighting spirit and daring leadership were an inspiration to his men and exemplify the highest traditions of the Armed Forces.

Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter, Jr.