In Memoriam

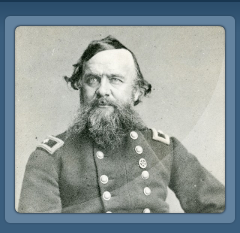

George Sears Greene,

Brevet Major-General, United States Volunteers

1801-1899

Published by authority of the State of New York, Under the Supervision of the

New York Monuments Commission

Albany

J.B. Lyon Company, State Printers

Dedication of Monument

Erected by the State of New York

in Commemoration of the

Services of

Brevet Major-General George Sears Greene

U.S.V.

and the New York Troops under his command

on the Battlefield of Gettysburg

July 2, 1863

September 27, 1907

Table of Contents Page

Introductory — Report of Monuments Commission - - - - 11

Dedication of Monument, September 27, 1907:

Military Parade — Program of Exercises on Culp's Hill - 21

Invocation by Reverend W. T. Pray ------ 25

Address by Major-General D. E. Sickles, U. S. A., Chairman - 27

Address by Colonel Lewis R. Stegman ------ 38

Address by Governor Charles E. Hughes ----- 49

Remarks by Brevet Major-General Alex. S. Webb, U. S. V. - - 52

Remarks by Major-General Frederick D. Grant, U. S. A. - - 53

Address by Governor Hughes to College Students, September 28, 1907 - 56

Life of General Greene:

Ancestry ---------- 61

Enters West Point 62

Resigns from the Army -------- 63

Re-enters the Military Service -------65

Services at the Battle of Cedar Mountain ----- 69

Maryland Campaign --------72

Chancellorsville -------- 78

Gettysburg 80

Wauhatchie 93

Final Campaign of Sherman's Army ----- 99

Mustered Out 100

In Civil Life 100

Placed on Retired List 101

General Greene's Family:

George Sears Greene, Jr. - - - - - - - -101

Samuel Dana Greene -------- 102

Major Charles Thruston Greene - - - - - - -103

Anna Mary Greene -------- 104

Major-General Francis Vinton Greene, U. S. V. - - - - 104

Lieutenant-Colonel William F. Fox, In Memoriam - - - - 108

Illustrations Portrait of Brevet Major-General George S. Greene - Bronze Tablet, south side ------- The Greene Monument -------

Bronze Tablet, north side ----.

Line of Greene's Brigade, Culp's Hill - - - - -

Portion of Greene's Brigade Line, Culp's Hill –

Battlefield of Gettysburg "88

In Memoriam

George Sears Greene

____

I n t r o d u c t o r y

BY Chapter 568 of the Laws of 1903, which became a law on May thirteenth of that year, this Commission was "authorized and directed to procure and erect on a site to be selected by them on the battlefield of Gettysburg, in the State of Pennsylvania, a bronze statue to Brevet Major-General George Sears Greene, deceased, at an expense not to exceed the sum of eight thousand dollars."

The monument erected by the State of New York, under the supervision of this Board of Commissioners by the provisions of the above-mentioned act, commemorates the services of General Greene and of the New York troops under his command, comprising the Sixtieth, Seventy-eighth, One hundred and second, One hundred and thirty-seventh and One hundred and forty-ninth regiments of infantry, forming the Third Brigade, Geary's division of Slocum's corps, and the Forty-fifth, Eighty-fourth, One hundred and forty-seventh and One hundred and fifty-seventh regiments sent to his support during the night of July 2, 1863.

By referring to sketches of the volunteer organizations of the State, given in "New York in the War of the Rebellion," it will be observed that the nine New York regiments commemorated were composed of companies principally recruited in twenty-six of the sixty-one counties of the State.

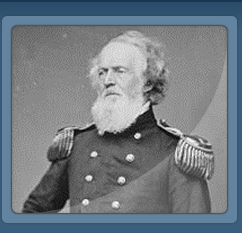

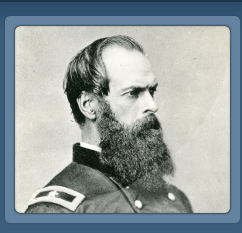

MAJOR GENERAL DANIEL E. SICKLES, U. S. A.

This page contains a photo.

Address General Daniel E. Sickles U.S.V. Chairman New Work Monuments Commission

Governor Hughes, Comrades and Guests:

THE Legislature of the State of New York, at its last session, authorized the New York Board of Monuments Commissioners to provide transportation to Gettysburg for fifty surviving veterans of each of the nine New York regiments that took part, under the command of General Greene, in the battle on Culp's Hill on the night of July 2, 1863, so that they could be present at the dedication of this monument, erected by the State to commemorate their services and the services of their commander.

I am glad to welcome these veterans — more than four hundred of them — who are here to-day. Forty-four years after the battle they meet again on their field of honor. May God bless them and spare them yet longer. They represent the Sixtieth, Seventy-eighth, One hundred and second, One hundred and thirty-seventh and One hundred and forty-ninth regiments of New York infantry, forming the brigade of General Greene; also the Forty-fifth and One hundred and fifty-seventh regiments of New York infantry sent to his support by Major-General Howard, commanding the Eleventh Army Corps, and the Eighty-fourth and One hundred and forty-seventh regiments of New York infantry sent by General Wads worth from his division of the First Corps.

The Commissioners were also authorized to invite the Governor of New York and such guests as he might ask to accompany him to attend this dedication. His Excellency Governor Charles E. Hughes is here with us on the platform. Among his guests are the Hon. James W. Wadsworth, Jr., Speaker of the Assembly, the grandson of Brevet Major-General James S. Wadsworth, who commanded a division in the battle of Gettysburg, and who was mortally wounded in the battle of the Wilderness, May 6, 1864; Captain John Raines, (p. 28) a veteran of the war for the Union, temporary President of the Senate; and Major-General Frederick D. Grant, of the United States Army, commanding the Department of the East, the eldest son of the late illustrious Ulysses S. Grant, General-in-Chief of the Army of the United States, and afterward President of the United States.

The Commissioners were likewise authorized to invite representatives of both branches of the Legislature to take part in the ceremonies of dedication, and we are also honored to-day by the attendance of Hon. William W. Armstrong, chairman, and the members of the Finance Committee of the Senate, and the members of the Ways and Means Committee of the Assembly.

We were, besides, authorized to extend invitations to the family of General Greene to witness the dedication of this statue of their distinguished kinsman. Of the descendants of the General there are twenty present, including his son, Major-General Francis V. Greene, late of the United States Army, and another son, Major Charles T. Greene, of the United States Army, who was an aide-de-camp on the staff of his father in the battle of Gettysburg, and who lost a leg in the battle of Ringgold, Ga., November 27, 1863.

The battle fought here by General Greene on the night of July 2, 1863, to hold possession of Culp's Hill, has a conspicuous place in history. It is memorable, not so much for the number of the combatants engaged as it is for the skill of the General, the heroic conduct of his troops, and in view of the consequences that would have followed the defeat of the Union forces. Greene was left here with a small brigade of 1,350 men to take the place of two divisions in defending the right flank of a great army. Eleven divisions of infantry had already been concentrated on the left flank. It is difficult to understand why the two divisions of the Twelfth Corps were ordered away from Culp's Hill to further reinforce the left flank; excepting a part of Lockwood's brigade, they did not fire a shot. The Sixth Corps was already there, but was held in reserve, and had not been engaged. Two divisions of the First Corps were sent from the right center to the left flank, but they were not put in action. The removal of the (p. 29) Twelfth Corps from the right flank was a grave error. The best efforts of Slocum, with eleven thousand men in a battle with seven brigades of the enemy, that began at dawn on the following morning and continued until eleven o'clock, were required to regain all the ground vacated by the corps the night before.

General Slocum, commanding the right wing of the army, made a wise selection in choosing Greene's Brigade to hold this important position. Its commander was an accomplished engineer, a skilful tactician and a resolute chief. His men were entrenched. He made all his dispositions with prudence and foresight. When the enemy advanced to the assault, with three times the force that Greene had, the Union commander was ready for the combat. He was ably supported by all his regimental leaders, one of whom—the gallant Colonel Lewis R. Stegman, of the One hundred and second New York — is with us to-day, I am glad to say. He will describe the battle. The rank and file, with supreme confidence in Greene, held their lines without flinching, pouring a sustained fire upon their assailants with destructive power. Again and again the assaults were renewed, only to be repelled with fearful loss. The battle raged for nearly three hours, when both sides rested on their arms until daybreak.

It is remarkable that General Ewell, who commanded the enemy's forces on their left flank, should have sent only one division to capture this very strong position on Culp's Hill, the right flank of our army, unless he was aware that the position had been seriously weakened by the withdrawal of the greater part of its defenders before the attack began. An hour before Johnson's Division advanced to make the assault, three divisions would have been easily repulsed by our Twelfth Army Corps, which then occupied Culp's Hill. Ewell was ordered by Lee to move against our right to aid Longstreet's attack on our left flank, which began at three o'clock in the afternoon, but Johnson's Division did not advance against Culp's Hill until near sunset — hours after Ewell was expected by Lee to attack. Johnson's advance was at once followed by an (p. 31) assault on Cemetery Hill. This assault was made by Early's Division, supported by the divisions of Rodes and Pender. Cemetery Hill was held by Howard's Eleventh Corps. How did it happen that Culp's Hill was attacked by only one division, while three divisions were assigned to the assault of Cemetery Hill, unless Ewell knew that Culp's Hill was defended by a small force, and that Cemetery Hill was defended by an army corps?

How Ewell could have been informed that all but one brigade of the Twelfth Corps had left their entrenchments and marched to the left of our line, two miles away, may never be known; at all events, no hint of it has ever transpired.

General Meade, in his testimony before the "Committee on the Conduct of the War," after referring to the troops of the Twelfth Corps from the right flank to the left, leaving only Greene's Brigade to hold Culp's Hill, says, "The enemy, perceiving this, made a vigorous attack upon General Greene." General Longstreet says in his "Manassas to Appomattox,"—" General Rodes discovered that the enemy, in front of his division, was drawing off his artillery and infantry to my battle on the right, and suggested to General Early that the moment had come for the division to attack." This citation shows that the enemy was aware of the withdrawal of troops on the right.

If the enemy could have secured this position, which dominated Cemetery Hill, the Confederate divisions of Early, Rodes and Pender were ready to seize that commanding height, on which their artillery would have made our line of battle on Cemetery Ridge untenable. Steuart's Confederate brigade had already occupied the vacated entrenchments on Culp's Hill, and were within a short march of our reserve artillery and the trains of the army, in the rear of Cemetery Ridge. The stubborn resistance of Greene alone saved us from disaster.

Strangely enough, the heroic defense of Culp's Hill was not mentioned in the official report of the commanding general of the Union Army. In this respect Greene was not more unfortunate than (p. 31) Gregg and his noble division of cavalry, whose successful battle with Stuart's Confederate cavalry on our extreme right, on the afternoon of July third, was likewise ignored. Greene's battle was afterwards brought to the notice of General Meade by General Slocum, when tardy recognition was accorded to Greene and his troops. Nor did Greene receive the promotion he had so well earned. He had already commanded a division at Antietam with distinction. He afterwards commanded a division in Sherman's army at the battle of Kinston, N. C. He was seriously wounded in the night battle of Wauhatchie, in Tennessee, under General Hooker. He was born in 1801, and was the oldest officer in the Army of the Potomac at the battle of Gettysburg; and he was the oldest officer in the army when he died, in 1899, in his ninety-ninth year. The famous General Nathanael Greene, so distinguished in our War for Independence, was his ancestor.

It was a source of great satisfaction to General Greene that he lived to see his four sons attain honorable distinction. George Sears Greene, Jr., his oldest son, attained prominence as a civil engineer in the aqueduct department of the city of New York and in railroad construction. In 1875 he was appointed engineer-in-chief of the department of docks in New York, and since 1898 has been a consulting engineer of that city.

Samuel Dana Greene, the second son, was graduated at the United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Md., in 1859. He became second in command of the ironclad Monitor. In the historic battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac, Lieutenant Greene had charge of the guns in the turret, every shot from which he personally fired until, when near the close of the fight, Lieutenant Worden being wounded, Lieutenant Greene took command of the vessel and pursued the Merrimac, driving her into the harbor of Norfolk. He was promoted lieutenant-commander in 1866, and in 1872 he was commissioned to the full rank of commander. He died in 1884.

Major Charles Thruston Greene began his military career as a member of the Twenty-second Regiment of the National Guard of (p. 32) New York in 1862. Soon afterwards he was promoted to a lieutenancy in the Sixtieth New York Volunteers, a regiment in which his father was for some time colonel. Afterwards he became an aide-de-camp on the staff of his father, then in command of the Second Division of the Twelfth Army Corps. He was present with his father at Gettysburg on July 2,1863, in the battle on Culp's Hill. While leading the Third Brigade, Second Division, Twelfth Army Corps, into action at the battle of Ringgold, in Georgia, November 27, 1863, he was wounded by a cannon-ball which killed his horse and severed his right leg. For gallant services he received the brevet commission of major, and was afterwards commissioned a captain in the Forty-second United States Infantry, commanded by General D. E. Sickles, being then only twenty-four years old, one of the youngest officers of his rank in the regular army. He was placed on the retired list December 15, 1870.

Major-General Francis Vinton Greene, the youngest of the sons, was graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, June 15, 1870, at the head of his class. He served for sixteen years in the regular army — in the artillery and in the corps of engineers. Resigning from the regular army in 1886, he was commissioned colonel of the Seventy-first Regiment of the National Guard of New York in 1892, a command he retained until his promotion during the war with Spain as Brigadier-General of Volunteers. He was given command of the second expedition to the Philippine Islands, arriving in Manila Bay July 17, 1898. After his services in the capture of Manila, he was made a Major-General of Volunteers to date from August 13, 1898. In September he was ordered to return to the United States and assigned to duty in Cuba as commander of a division in the Seventh Army Corps. He resigned from the army February 28, 1899.

Anna Mary Greene, the only daughter of General George Sears Greene, married Lieutenant Murray Simpson Day, United States Navy, a son of Brigadier-General Hannibal Day, of the United States Army, a classmate of General Greene in 1823. During the (p. 33) latter days of his long life General Greene made his home with his daughter, Mrs. Day, at Morristown, New Jersey.

New York may always remember with satisfaction the distinguished part borne by her soldiers on this memorable field. In the battle of July first our six divisions of infantry were all led by New York commanders — Doubleday, Wadsworth and Robinson, of the First Corps, and Schurz, Von Steinwehr and Barlow (wounded), of the Eleventh Corps. Brigades of infantry were commanded by Von Gilsa, Coster, Von Amsberg and Krzyzanowsky, all of New York. Wainwright and Osborn, of New York, were chiefs of artillery, and Devin, of New York, commanded one of the cavalry brigades of Buford's division. Doubleday took command of the First Corps when Reynolds fell.

In the battle of July second, the right and left flanks of our army were held by the Twelfth and Third Army Corps, commanded, respectively, by Slocum and Sickles, of New York. The brigades of Ward, De Trobriand, Graham, Carr and Brewster, of the Third Corps, the brigades of Zook, Willard and Kelly, of the Second Corps, Ayres' division and the brigades of Weed and of Rice (who succeeded Vincent), of the Fifth Corps, all New York commanders, sustained the many fierce combats that ended in the final repulse of the enemy on our left flank. Of these leaders, Zook, Weed and Willard were killed, and Sickles and Graham wounded.

The heroic Greene of the Twelfth Corps, with a brigade of five New York regiments, supported by four others sent him by Howard and Wadsworth, firmly held our principal entrenchments on Gulp's Hill against the persistent assaults of a division of the enemy, under Johnson.

Among the commands prominent in the events of the third day, when Lee made his desperate attempt to retrieve the fortunes of a lost battle, were the brigades of General Alexander S. Webb, of the Second Corps, and of Shaler, of the Sixth Corps, both of New York; the latter included three New York regiments, and helped Slocum recover our line on Culp's Hill. And when Webb's brigade met the (p. 34) shock of Armistead's Virginians on Cemetery Ridge the enemy had fired his last shot. And Kilpatrick, commanding a division of cavalry, of whose movement on the third Longstreet says: "Had the ride been followed by prompt advance of the enemy's infantry in line beyond our right and pushed with vigor, they could have reached our line of retreat."

The commanders of the Second and Fourth Volunteer Brigades of Artillery Reserve—Captains Taft and Fitzhugh—were also New Yorkers; and Russell, Bartlett and Nevin, in command of brigades of the Sixth Corps, in reserve.

Besides the Chief of Staff, General Butterfield (wounded), and the Chief of Engineers, General Warren, three army corps, eight divisions and twenty-five brigades, led by New York commanders, were all engaged in the battle of Gettysburg.

More than forty thousand men fell on this field. On our side we had 85,000 in the battle; of these, New York contributed 27,692. The loss in the Union Army was 23,049, of which 6,773 was borne by New York troops. The State of New York provided 482,313 men for the Union Army; of this vast number 53,000 died in service. Of the three hundred renowned battalions whose losses in killed and wounded were the largest, as shown by Fox, the historian, fifty-nine regiments were New York troops. From 1861 to 1865 the State of New York expended $125,000,000 in raising and equipping its forces. New York regiments and batteries fought in more than a thousand battles, engagements and skirmishes. Apart from those on this battlefield, hundreds of naval and military monuments are already placed in as many towns and cities in our State.

In all ages of the world's history, and in all countries, the admiration of the people for their military and naval heroes has sought expression in costly monuments built in honor of great commanders. In this country the disposition is to exalt the virtues and services of our citizen soldiers, upon whom the brunt and burden of our Civil War mainly fell. Eighty-six regimental and battery monuments, (p. 35) erected on this field by the State of New York, will have a touching interest for all time to our citizens, and, above all, to the descendants of the men who served in our New York commands.

Gettysburg was a decisive victory, won at a moment when defeat might have been ruinous to our cause. It marked the beginning of the decline and fall of the Southern Confederacy. Our success here was gained over the most formidable army ever encountered by the Union forces. The advance of General Lee to the Susquehanna marked the extreme limit ever reached by the invading forces of the South.

By common consent this famous battlefield has been chosen to signalize the patriotism, fortitude and valor of the defenders of the Union in the great Civil War. Eighteen states have erected memorials on this field to honor the services of their citizens. Four hundred and fifty monuments have already been placed here, and the list is not yet completed.

It cannot be said that our people have been unmindful of the merits of our conspicuous military and naval leaders, but I sometimes fear that the public regard has waned somewhat toward the rank and file of the armies and fleets that saved the Union. Let all of us who are here to-day, in the presence of so many heroes who defended this height from the assaults of aggressive and gallant foes, remember, as Lincoln said, that "There is one debt the American people can never pay, and that is the debt they owe to the soldiers on the field of battle who saved our Union."

These occasions remind those who fill the executive chambers and legislative halls of our State of the perils, sacrifices and sufferings of the brave men who carried the muskets and who stood behind the guns on this battlefield. What would have happened if they had failed? Imagine the havoc, the ruin and desolation that would have followed the march of a victorious enemy through Pennsylvania to the Delaware, and the recognition of the Southern Confederacy by the European powers and their intervention to stop the war.

These brave men who are now present, and their comrades, remind this generation of the debt it owes to the soldiers who (p. 36) won the victory for the Union, not only for themselves, but for the millions who enjoy the fruits of the triumph gained at the cost of so many thousands of lives.

Let us hope that when these survivors of the nine New York regiments who saved Culp's Hill return to their homes, fresh from a new consecration at Gettysburg, they may find in their fellow citizens in the towns and villages and cities where they live a renewal of the respect, esteem and admiration they received in the old days of 1865, when a restored Union and an enduring peace were the priceless gifts they bore to their families and friends and neighbors at home.

On this occasion I am disposed to close my address — the last I shall make on this battlefield — by adopting as my own the words of the Right Reverend Henry C. Potter, then bishop of New York, taken from the oration delivered by him at Gettysburg on New York Day, July 2, 1893. The bishop said, in commending to the people of our State and to their representatives the obligation and duty of caring for our surviving veterans of the Civil War:

"They wore our uniform. By cap, or sleeve, or weapon, somewhere, there was the token of that Empire State whence they came— whence we have come—and that makes them and us, in the bond of that dear and noble commonwealth, forever brothers. And that is enough for us. We need to know no more. From the banks of the Hudson and the St. Lawrence, from the wilds of the Catskills and the Adirondacks, from the salt shores of Long Island and from the fresh lakes of Geneva and Onondaga, from the forge and the farm, the shop and the factory, from college halls and crowded tenements, all alike, they came here and fought, and shall never, never be forgotten, our great unknown defenders!

"Do you tell me that they were unknown, that they commanded no battalions, determined no policies, sat in no military councils, rode at the head of no regiments? Be it so! All the more are they the fitting representatives of you and me, the people. Never in all history, I venture to affirm, was there a war whose aims, whose (p.37)

policy, whose sacrifices were so absolutely determined by the people, that great body of the unknown, in which, after all, lay the strength and power of the Republic.

"And is not this, brothers of New York, the story of the world's best manhood and of its best achievements? The work of the great unknown for the great unknown — the work that by fidelity in the ranks, courage in the trenches, obedience to the voice of command, patience at the picket line, vigilance at the outposts, is done by that great host that bear no splendid insignia of rank and figure in no commanders' despatches — this work with its largest and incalculable and unforeseen consequences for a whole people, is not this the work which we are here to-day to commemorate?

"Ah! my countrymen, it was not this man nor that man who saved our Republic in its hour of supreme peril. Let us not, indeed, forget her great leaders, great generals and great statesmen; and, greatest among them all, her great martyr and President — Lincoln. But there was no one of these who would not have told us that which we may all see plainly now, that it was not they who saved the country, but the host of her Great Unknown. These, with their steadfast loyalty, these with their cheerful sacrifices, and these, most of all, with their simple faith in God and the triumph of His right —These were they who saved us! Let us never cease to honor them and care for them."

Address by Colonel Lewis R. Stegman

102d New York Vols.

_______

Boys of the Old Brigade, and All the Boys Who Wore the Blue:

THIS is a memorable occasion for the survivors of Greene's Brigade, and for all the boys who fought on Gulp's Hill, in the fact that we are permitted to be present at the unveiling of a statue to our heroic commander, General George Sears Greene, honored, respected and beloved by every man who carried a musket or sword under his orders. In our camps he was a father in his care for the boys. On the battle lines his form was ever at the front. His presence was an inspiration. He was a perfect soldier, believing in the American volunteer, and the volunteer believed in him. And glad are we that the State of New York has honored his memory by this magnificent statue of bronze.

The battle of Gettysburg was a series of episodes, as all battles are, and right here, on Culp's Hill, occurred one of the great episodes which go to make up the history of this tremendous and significant conflict. On this spot, on the night of July 2, 1863, under the direct command and supervision of General Greene, his troops fought in defense of this hill with such obstinacy and determination that the enemy were repulsed in four terrific attacks, leaving Greene the victor.

Let us revert for a moment to the day of the battle here and survey the situation:

Immediately to the southwest, within twenty minutes on the double-quick to an alert soldier, lay the headquarters of the commander-in-chief on the Taneytown road, and the center of the Union Army, under Hancock, while directly to the rear of this brigade, across the Baltimore Pike, lay the reserve ammunition trains and reserve artillery of the Army of the Potomac, possibly five hundred (p. 39) This page contains an image. yards away. To protect this front, the right of the Union line, the Twelfth Corps, Slocum's, was assigned. It was temporarily under the command of General Alpheus S. Williams, "Old Pop Williams" as he was familiarly termed, for Slocum had been placed in charge of a grand division composed of the Fifth and Twelfth Corps. Just to the left of the Twelfth Corps, on this ridge of Culp's Hill extending northwesterly, lay Wadsworth's division of the First Corps, while, in extension, part of the Eleventh Corps had established a line leading over Cemetery Hill. Greene's Brigade of New York regiments, the Sixtieth, Seventy-eighth, One hundred and second, One hundred and thirty-seventh and One hundred and forty-ninth, numbering 1,350 muskets and seventy-four swords, occupied this front, extending from the apex of Culp's Hill, southerly, to a gentle swale on the right of the line where Kane's Pennsylvania brigade covered the ground, joining the First Division, which continued the extension to Wolf's Hill, past Spangler's Spring, forming the extreme right of the whole Union Army infantry line. Candy's First Brigade was in reserve. Several miles beyond were Union cavalry as outposts. Greene's Brigade was the left of the Twelfth Corps.

Directly to the northeast of this position, a half mile or more distant, is Benner's Hill, running parallel to Culp's Hill but less high and prominent. On Benner's Hill lay Johnson's Division of Ewell's corps of Confederates, a corps that only two months before had been commanded by the redoubtable "Stonewall" Jackson. This division was composed of the original troops that had made Jackson famous, and particularly his old brigade, whose bravery had gained for him the sobriquet of "Stonewall." More gallant soldiers than these old veterans did not exist in the Southern service. They believed themselves invincible. Johnson's Division included four brigades: Jones' Virginians, Twenty-first, Twenty-fifth, Forty-second, Forty-fourth, Forty-eighth and Fiftieth regiments; Nicholls' Louisianians, First, Second, Tenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth regiments; Steuart's North Carolinians, First and Third regiments; Virginians, Tenth, Twenty-third and Thirty-seventh regiments, and a battalion (p.40) of Marylanders, the First battalion; and Walker's, the old Stonewall Brigade, of Virginians, Second, Fourth, Fifth, Twenty-seventh and Thirty-third regiments. Four batteries — Brown's, Dement's, Carpenter's and Raine's — comprised the artillery force. There were twenty-two regiments in the division. They had occupied Benner's Hill from the afternoon of July first, when they took possession of it, after the first day's fight, in which they had not participated, and consequently were fresh and ready for any duty they might be called upon to perform.

To more thoroughly appreciate the position occupied by the Confederate troops, it may be here stated that, by order of General Meade, the commander-in-chief, General Slocum, with General Warren, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac, had made a preliminary survey on the morning of the second of July of the enemy's position in contemplation of an attack by the Fifth and Twelfth Corps, to be supported by the Sixth Corps; but both officers reported against such a movement, based upon the strength of the enemy's position and the difficulties of such a movement. The numbers and position of the Confederate forces were fully explained to the commander-in-chief and the proposed attack was abandoned. It will be well to recall this report, for when, later in the day, Greene's Brigade defended and held this position, not a single Confederate soldier who had been on Benner's Hill in the morning, when Slocum and Warren reported against such an attack, had been withdrawn. They were all there. About four o'clock on the afternoon of July second, right here where we stand, occurred a sharp artillery duel. Knap's battery of Geary's division, commanded by Lieutenant Geary, the General's son, and Battery K, Fifth United States Artillery, Lieutenant Van Reed, made a magnificent defense. When the artillerists on the guns were shot dead or wounded the lads of the Sixtieth and Seventy-eighth New York, then lying around here supporting the guns, took the places of the artillerists and worked them so skilfully and bravely that they were complimented by the artillery officers. (p. 41) The Confederate batteries were silenced, driven back, and one of their best beloved officers, young Latimer, known as the "Boy Major," was killed. It was the only Confederate artillery directed upon this point, Culp's Hill, during the battle.

While this duel was going on, there came ominous sounds from the southwest, the left wing of the army. The crash of artillery and the frightful roar of musketry made it certain that deadly work was going on there. The volume of sound kept increasing, and it was evident that a murderous battle was on. It was Longstreet's desperate attack on the position of the gallant little Third Corps, commanded by the magnificent Sickles, and extending from the Peach Orchard to the Devil's Den, and later following the angle of the Emmitsburg road. The Fifth Corps was moved over to the relief of the small band who were endeavoring to hold the lines, followed by Caldwell's division of the Second Corps; and, finally, General Meade became so anxious in regard to the defense of the left wing that he ordered the whole of the Twelfth Corps to vacate its position here on the right and to hurry to the rescue of the left. General Williams, commanding the corps, ordered his old division under General Ruger to move, leading them in person, and soon thereafter Geary was ordered to follow with his division, by order of General Slocum, retaining one brigade to defend the whole corps line. That brigade was Greene's, the left of the division; Kane and Candy, with the First and Second Brigades, going with General Geary southeasterly toward Rock Creek, on the Baltimore Pike, where they halted.

And here one word of encomium for the prescient eye and brain of our noble Slocum. When he was ordered to take the whole of the Twelfth Corps to the left he protested to General Meade that his advices from General Williams and General Geary were to the effect that the enemy were in strong numbers in their front, ready for an attack. He requested General Meade to be permitted to keep General Geary's division to cover the works of the corps, not to leave them deserted. Then General Slocum says, "I was permitted to retain one brigade, and I retained Greene's." Thus it happened (p. 42) that by the sagacity of Slocum, Greene's Brigade was selected to defend this hill, this position.

When Greene's Brigade arrived at this point on the morning of July second, having been relieved from duty on the extreme left of the army, under the Round Tops, where it had been assigned on the evening of the first day of the battle, it joined its comrades of the division and the corps. Immediately on its arrival, by order of General Greene, who personally superintended the work, the men commenced to construct earthworks, if they may be so called, composed of logs, cordwood, stones and earth, about breast high, a good protection against ordinary musketry. The works were finished by noon. The whole corps line, also Wadsworth's division, followed with works, and the right wing was ready for the attack. This brigade, for the first time in its battle history, had constructed earthworks at Chancellorsville. By reason of a flank attack, made by this same Stonewall Jackson's corps, which lay out in the front here, the brigade had been driven back, regiment by regiment, fighting on regimental fronts. This first attempt to use earthworks having proven so futile and without benefit, the men of the brigade were not anxious about the works here. But they obeyed orders, particularly as General Greene walked along the lines with care, giving personal direction as to the measurements and the angles. Many a man who sits before me to-day grumbled that morning and afternoon at the persistency of "Pop Greene," their term of endearment, and prophesied that they would have their labors for their pains. Before many hours they rendered thanks and blessings for the skilful plans and judgment of their beloved commander. It seldom happened in their future career that earthworks were necessary, but the men of this brigade were never loath, after Gettysburg, to throw up all the works that might be necessary to defend any position occupied.

It was nearly six o'clock on the evening of July second that the order for Geary's division to move was received — that is two brigades, Candy's and Kane's — leaving Greene to stretch out his thin line over all the space formerly occupied by the corps to (p. 42) make as good a showing as possible. As soon as Geary had led his men away, General Greene commenced to make dispositions to cover the space rendered vacant. The regiments of the brigade then lay along the line as follows: On this hill, joining Wadsworth's division, was the Seventy-eighth, then the Sixtieth, part of its front down the hill; the One hundred and second, at the foot of the hill, forming the center; the One hundred and forty-ninth next, while the right of the brigade was occupied by the One hundred and thirty-seventh. This was the position of the brigade when the firing of the skirmish line in front, over beyond Rock Creek, some two or three hundred yards down the hill in this front, became more acute than it had been during the earlier part of the day. Firing had taken place between the two skirmish lines at different hours during the day, and the Union boys had driven the Confederates close to their main line of battle. But at seven o'clock the order of attack was reversed; the Confederates had strengthened their skirmishers and they came booming. Greene's Brigade skirmishers held them nobly. Lieutenant-Colonel Redington, of the Sixtieth, who had command of the line and had given his orders by bugle, blew for assistance, and the Seventy-eighth was taken from this immediate front and rushed down the hill and through the ranks of the One hundred and second to his relief. Redington had fallen back slowly, contesting every inch of ground so sturdily that the Confederates, in their official reports, speak of driving lines of battle. The skirmishers were already at Rock Creek when the Seventy-eighth reached them. The regiment received and delivered several volleys, when it became evident to Colonel Hammerstein that he was facing a superior force. He ordered the regiment to fall back into the works, joining the One hundred and second as a right wing. All the skirmishers who were not killed or wounded came rapidly to the rear.

While this skirmish firing was going on, and after the Seventy-eighth had gone to their assistance, the balance of the brigade commenced to move to the right, except the Sixtieth, which had (p. 44) to cover the interval left by the Seventy-eighth on this front and to cover its original line down the hillside. The One hundred and second moved into the One hundred and forty-ninth works, while the One hundred and forty-ninth moved into the works of the One hundred and thirty-seventh, the latter moving into Kane's brigade works, part of Geary's division line. In the movement the men had taken position fully a foot apart. There were not men enough to cover the ground they had been ordered to hold, and what should have been a strong line of battle was practically only a strong skirmish line. The extension had not been completed, and it was already dark in the dense and murky woods, when the Seventy-eighth and the regular skirmishers came over the works hotly pursued by the enemy.

Let us revert here for a moment to the Confederate line to fully comprehend the import and strength of the attack on this position. Early in the day, according to General Lee's plan, there was to have been a simultaneous attack made upon the right and left wings of the Union Army. Sickles and Slocum were both to be forced from their strongholds, and by their destruction the whole Union Army put to rout. Longstreet was to force Sickles, while Ewell was to master this point. The opening of the engagement on the left was to be the signal for Ewell's advance here. Whatever the reason, Ewell did not advance at the time specified. If he had done so he would have found the whole Twelfth Corps in the line of defense. He postponed his attack until only Greene's Brigade was left on the Twelfth Corps line.

It is a matter of interest here to note an important point. When the First and a part of the Second Division of the Twelfth Corps were ordered to abandon their positions on the line, according to the official records, the strong force of skirmishers which had covered their fronts were also withdrawn, the men rejoining their respective regiments, and proceeding with the main bodies to the relief of the left wing. It should be recalled that this skirmish line had been observing the enemy all day long, and at the same time had (p. 44) been observed by the enemy. When it was suddenly called back, it must have attracted the attention of the enemy at once, and efforts to discover the cause have been made. This would reveal that the main force had been withdrawn, and that only a part of the troops originally stationed on the line were in occupation of this hill. Alert officers on the Confederate skirmish line could and probably did convey this important information to the commanders on Benner's Hill, only a short distance to the northeast. That this knowledge of the situation was in possession of General Johnson, the Confederate division commander, seems almost certain from the method and manner of his attack on Culp's Hill. His whole force in the attacks was concentrated directly upon this point. He made no attempt to spread his lines to cover the corps position. Had the whole corps been there his position would have been hazardous, for his left flank would have been in immediate danger of being overwhelmed. As it was, Johnson's left was free, and from the first moment to the last engaged in the severe encounters on this front. Johnson's four brigades, in ordinary battle line, could have covered the whole front of the Twelfth Corps, a small corps on this field. As it was, three brigades came directly at this hill, determined to crush the depleted right wing. That they failed was due to the splendid skill of Greene and the desperate resistance offered by the troops under his command.

When Johnson's Division started from Benner's Hill, Jones' Virginians led the column, being the first to advance. As they developed, Nicholls' Louisianians formed on their left and immediately thereafter Steuart's North Carolinians and Virginians, with the Maryland battalion, formed further to the left, a magnificent battle array of seventeen regiments, veterans of proved merit. They were three lines deep. These were the troops that the Union skirmishers had met, before whose massive numbers they had fallen back. As they advanced and took position, firing by volley or at will, they aligned before these works in the same order in which they advanced — Jones directly under the hill, the Sixtieth line, (p. 46) charging the front, Nicholls in the center, fronting the Seventy-eighth, One hundred and second and One hundred and forty-ninth, while Steuart, further to the left, covered the One hundred and thirty-seventh, all advancing in the fury of heated combat. All parts of the line were engaged.

As previously stated, the lines of Greene's little brigade of five regiments had not been formed; the men were still moving to take more ground to the right when the storm struck them. Further extension was abandoned. The endeavor to hold the unoccupied works was given up in the necessity of fighting for their lives and the position they held. The men in march halted and faced the foe.

Twilight and the murky darkness of the woods rendered the scene one of extreme impressiveness. The rebel yells, the "hi-yi" so familiar in many a battle, came ringing from the density below, and with it volleys of musketry. The blaze of fire which lighted up the darkness in the valley, the desperate charging yell and halloa of the Confederate troops, convinced the boys of Greene's Brigade that an immediate engagement was on. They faced the emergency as became good soldiers, their volleys ringing in fierce reply to the Confederate offense. They battled with the determination that makes success. There were no heroics on the line except in the stern duty well done. For hours, the crash of musketry was unceasing; three hours of conflict with rifle-balls at close quarters. And at the end the enemy had fallen back. Four times, with desperate yells, with the determination to carry these works at all hazards, had the Confederates charged; four times they went back discomfited. They had charged clear to the works, so close that they made attempts to grasp the regimental flags, and died as their hands clutched for the colors. They built breastworks of their own dead on this brigade front, so merciless was the Union fire; and the men who so used their comrades' bodies were killed behind them.

General Jones, of the Confederates, was early wounded in this immediate front, and Lieutenant-Colonel Dungan assumed command of the brigade. The official reports show a heavy loss. Nicholls (p.47) suffered severely; and on the right, in front of Steuart, the dead lay thick. To account for this defeat, the Confederates, in their reports, speak of forts which they attacked, and of the overwhelming numbers against whom they fought. The numbers they fought were the little regiments of Greene's Brigade, and the splendid though decimated regiments which came to their assistance in the stress of the battle.

General Greene early in the engagement perceived the necessity of reinforcements and called for succor from the forces nearest at hand. To his aid were sent the Fourteenth Brooklyn (Eighty-fourth New York) and the One hundred and forty-seventh New York from Wadsworth's division, which hurried to the right of the line in time to help the One hundred and thirty-seventh in repelling a savage attack by Steuart's Brigade, then enveloping the right flank. They did magnificent service that night, which was continued until the next day by the Fourteenth Brooklyn. On other parts of the line came the Sixth Wisconsin from Wadsworth, men of the First Corps, while the Eleventh Corps sent its gallant Forty-fifth New York, the One hundred and fifty-seventh New York, the Eighty-second Illinois and the Sixty-first Ohio to aid their comrades of Greene's Brigade in the defense of the position. How well they did their work is attested by the enemy's dead who lay where our rifles carried destruction. To our men all honor. Where all our regiments did such noble duty as was done here, no distinctions of merit can be drawn. They performed their full duty as soldiers.

Just here, at the apex of this hill, men of the Sixtieth rushed over the works and captured two Confederate battle-flags and took prisoners. Over on the right, Lilly, the color-bearer of the One hundred and forty-ninth, twice spliced the flag of the regiment when the staff was shattered in the hail of Confederate bullets, and the flag that he bore carried eighty wounds in its folds to show where the merciless shot had rent it.

By ten o'clock the main fight here had ceased. The terrific musketry had died down. The four shocks of the enemy against this line had failed. He fell back across the creek, leaving only a (p. 48) small force to protect his front. Greene had held this line: not one foot of the original works had been crossed by a Confederate, except as a prisoner. The flags of the Union line were intact; the Union line had captured Confederate colors. The right was secure for the night.

One moment of review of the forces engaged. On the Union side there were Greene's Brigade of 1,424 officers and men; from the First Corps about 355 men, and from the Eleventh Corps about 400 men, for it must be recalled that the regiments of these two corps had been in the first day's fight and had been depleted to a fearful extent. Thus, on the defensive line there had been about 2,000 men comprised in twelve small regiments. On the Confederate side there were seventeen organizations. Their strength is not given. One regiment defines its strength as 270 and its loss at nearly three-quarters; another as 350, with heavy losses. So it may be safe to average the regiments engaged at 300 each, giving a force of over 5,000 Confederates in attack.

Deeds of heroic valor were performed upon every part of this field during its three days of merciless fighting. The dauntless defense of Seminary Ridge on the first day by the First and Eleventh Corps; the magnificent courage of the Third Corps from the Devil's Den to the Peach Orchard and on the Emmitsburg road on the second day; the saving of the Round Tops by the Fifth Corps, and the surpassing battle of Webb's brigade at the "Bloody Angle" on the third day, are all themes of song and story, splendid episodes of American daring. But nowhere upon this field was more dauntless heroism displayed than in the defense of Culp's Hill by the men of Greene's Brigade and those who assisted them on the night of July 2, 1863.

Slocum says of the night fight: "The failure of the enemy to gain entire possession of our works was due entirely to the skill of General Greene and the heroic valor of his troops." What higher encomium can be asked for than that of our peerless corps commander?

Page 49

Address by Governor Charles E. Hughes

______

General Sickles, Fellow Countrymen:

WE have come to this field of eloquent memorials to pay a deserved tribute to one who, in supreme test, vindicated his manhood and his leadership. We are here as New Yorkers to commemorate the fidelity and valor of a son of New York. We have met as citizens on this consecrated soil, where, in severest conflict, the heroism of two armies glorified the American name, and in the victory of one was found the sure promise of a restored Union and of the happiness of these later years.

You survivors of battle, in diminished ranks, mourning your comrades, and yet rejoicing in the memory of those heroic days, have gathered here to-day in honor of the brave leader under whose command the desperate engagement on this hill was fought.

Veterans: To you these stones are quick with life. You live again in the comradeship of war; and those who fell here, and those who lived to fall elsewhere, are once more by your side. Each bit of ground has its story of daring, of resolute defense, of suffering, of death. Here in patriotic devotion you offered your lives, and the memory of your steadfastness at Gettysburg and on Culp's Hill in that dark hour is one of the choicest of our national treasures.

The Civil War was not more notable for its political consequences than it was for its revelation of the quality of our citizenship. Priceless as is the national unity which was gained through that struggle, the value of that unity rests upon that sterling character and the capacity for heroic effort, which, in both North and South, found abundant illustration. The virtues displayed on either side of that fierce contest are the common heritage of a united people. And alike in heroism upon the battlefield, in fortitude, in the untold sacrifices of those that remained at home, in the skill, in the discernment, in the energy of leaders, in the discipline, readiness (p. 50) and valor of the troops they led, stood revealed the splendid pertinacity, the inflexible determination and the moral forcefulness of American manhood.

General Sickles: New York is more proud of the manner in which it met that test than it is of its wealth or its broad domain. As you have said, New York sent 400,000 of its sons to the Northern Army— one-fifth of its male population. In every part of this field are the records of New York troops — records of fidelity and honorable achievement. As we have just learned in the eloquent words of Colonel Stegman, at a critical moment the boys of Greene's Brigade held firm under an attack, made the more terrible by the darkness which covered the earth, from an invisible, superior force. They held firm and by heroic defense protected the safety of the army; and, to their alert, sagacious General, we, the sons of the Empire State, erect this monument, expressive of our love, expressive of our pride, expressive of our lasting obligation. (Applause.)

The generation which fought here has almost passed away. The distinguished leaders still with us, and in whose presence we rejoice to-day, recall to us the more vividly those who have already gone from us. Their sacrifices were not in vain. Those who died here did not die in vain. The same national character which accounted for the fierceness of that strife, in whose devouring flames were displayed the indestructible riches of moral strength, is ours to-day. The same patriotic ardor fills the breasts of American youth as when they rushed from field and factory and college at their country's summons. The wives and mothers of America are as loving, as devoted, as ready to sacrifice and to suffer as were those of forty odd years ago. (Applause.) The men of the United States are as quick to respond to the call of duty, as keen, as resourceful, as valiant as were those of our heroic past. They are blessed with the memory of your labors; they are enriched with the lessons of your zeal; forever will they be inspired by the example of your patriotism.

We are engrossed to-day in the pursuits of peace. Mind and nerve are strained to the utmost in the varied activities which promise (p. 51) opportunity for individual achievement. But the American heart thrills at the sight of the flag; the American conscience points unwaveringly to the path of honor; the American sense of justice was never more supreme in its sway; and, united by a common appreciation of the ideals of a free government, by a common recognition of the riches of our inheritance, by a common perception of our national destiny, the American people should, and we believe will, go steadily forward, a resolute, a happy, resourceful and triumphant people, enjoying in ever greater degree the blessings of liberty and union. (Applause.)

Life and Military Services

of

Brevet Major-General George Sears Greene

U.S.V.

________

By William F. Fox, Lieutenant-Colonel U.S.V.

Page 61

THE manly, heroic virtues which have given the American soldier an honored place in military annals were inherited largely from the men who formed the early emigration to the American colonies. The emigrants in those days were, of necessity, resolute, fearless and self-reliant. They were men who, rather than submit to oppression, would bid good-bye to home and native land, brave the dangers of the sea and make their abiding place in a new and untried country. The women who shared their fortunes possessed the same sterling traits of character, and were well fitted to become the mothers of a race of soldiers.

It has been said of the pioneers, who, from 1620 to 1660, left England for the new world, that "they were stanch supporters of the rights of the people, and with them departed the very heart of England's manhood." Grapes are not of thistles, nor figs of thorns. Like begets like, and these men, possessing all the traits of character that go to make the ideal soldier, were the progenitors of a fighting race that was to stand undaunted at Lexington and Gettysburg. In this study of heredity a conspicuous example is found in the great soldier whose life forms the subject of these pages.

In 1635 John Greene, a gentleman of good family in Salisbury, England, bade farewell to the land of his birth, and, crossing the stormy Atlantic, joined the Massachusetts Bay Colony. A few years later he allied himself with Roger Williams in establishing a colony in Rhode Island, and settled at Warwick in that province where his son John became, in time, the Lieutenant-Governor. Among his descendants in successive generations were men holding (p. 62) prominent offices in the colony — Governor, Lieutenant-Governor, United States Senator and Judge of the Supreme Court. Two of them — Major-General Nathanael Greene and Colonel Christopher Greene — achieved great distinction in the army during the War of the Revolution.

In the seventh generation there was born, in the village of Apponaug, Rhode Island, on May 6, 1801, George Sears Greene the distinguished soldier whose biography follows here. He was the son of Caleb and Sarah Weeks Greene and a grandson of Caleb Greene. His father was a ship-owner who resided in the village of Apponaug, in the town of Warwick, where he owned several hundred acres, a part of the large tract which his ancestor, the first John Greene, had purchased from the Indian Chief Miantonomoh in 1640. Caleb Greene had nine children, of whom four died in infancy, and the other five lived to be more than eighty — George Sears Greene attaining the age of ninety-eight.

Young Greene, having completed his preliminary education in the grammar school at old Warwick, went to the Latin school in Providence with the intention of entering Brown University; but owing to financial reverses in the family, it became necessary for him to earn the money with which to complete his education, and so he secured employment in the office of a dry-goods merchant in New York City. While employed there he received an appointment as a cadet at West Point. It is noted in the family records that he made the journey from New York City to the military academy on the Hudson in a small sailing vessel — the best available means of transportation in 1819.

Entering West Point at the age of eighteen, he was graduated in 1823 with high honors, standing second in his class, a class which numbered seventy-nine members at its entrance. Among the cadets who were in the academy during his four-year term, and who became distinguished were Mansfield, Hunter, McCall, Mordecai,

BRONZE TABLET. Placed on northerly side of granite pedestal.

This page contains an image.

(p. 63) Lorenzo Thomas, Day, Mahan, Bache, Anderson, C. F. Smith, Bartlett, Albert Sidney Johnston, Heintzelman and Casey. On graduating, he joined the army as a brevet second lieutenant in the First Artillery, from which he was soon transferred to the Third. At the expiration of the usual graduating furlough he was assigned to duty at West Point as an assistant professor of mathematics, a position which he held for nearly four years, after which he was stationed at various artillery posts. A promotion to a first lieutenancy was received May 31, 1829.

In the summer of 1828 he was married at Providence to Elizabeth Vinton, whose brother, David H. Vinton, had been in the class before him at West Point, and was one of his most intimate friends. She bore him three children, two sons and one daughter; but all of them, together with their mother, died within a period of seven months at Fort Sullivan, in 1832 and 1833. From such an overwhelming calamity the only possible relief from the monotony of garrison life at a small and remote station was found in intense study; and during the next three years he read exhaustive courses in law and medicine, qualifying himself to pass examinations admitting him to practice in either of these professions. He also continued the studies in engineering which he had pursued at all times since his graduation at West Point. In the autumn of 1835, being still, after more than twelve years' service, a first lieutenant of artillery, he determined to resign from the army and engage in the practice of the profession of civil engineering. He obtained leave of absence until June 30, 1836, at which time his resignation was to take effect, and began work as an assistant engineer on the railroad from Andover to Wilmington, in Massachusetts, the small beginning of what is now the great Boston & Maine Railroad system.

"While thus employed he was frequently in Boston and Charlestown; but it was while she was on a visit to Maine, in company with her father, that he met his second wife, Martha Barrett Dana, daughter of Hon. Samuel Dana, who had served for several terms (p. 64) in the Assembly, the State Senate, and in Congress. He was of the well-known Dana family of Massachusetts, descendants of Richard Dana who came from England to Cambridge in 1646. They were married in Charlestown, Mass., on February 21, 1837, a happy union that lasted until her death forty-six years later."* Of the six children by this marriage, one died in infancy, five grew to maturity and four survived their parents. Three of the four sons served in the military or naval service of their country in time of war. The children were:

George Sears Greene, Jr., born November 26, 1837.

Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene, United States Navy, born February 11, 1840; died December 11, 1884.

Major Charles Thruston Greene, United States Army, born March 5, 1842.

Anna Mary Greene, born February 19, 1845.

James John Greene, born September 4, 1847; died October, 1848.

Major-General Francis Vinton Greene, United States Volunteers, born June 27, 1850.

General Greene soon achieved a distinction in his profession as a civil engineer that created a constant demand for his services. Much of his time was devoted to railway construction, during which he built railroads in Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New York, Maryland and Virginia. In 1856 he was connected with the Department of Water Supply in the City of New York, and during his service in that position he designed and constructed the large reservoir in Central Park. The enlargement of High Bridge was also his design, and the work was done under his supervision.

In 1861, when it became evident that the Civil War was to be something more than a militia affair, Greene tendered his services to the Governor of New York. There was some delay on the part of the State authorities in providing for him an appointment suitable

*From Memoir of George Sears Greene. By his son, Francis Vinton Greene. New York, 1903. 64

(p. 64) to his military experience and ability. But on January 18, 1862, he was commissioned Colonel of the Sixtieth New York Volunteers, and he re-entered the military service of his country at the age of sixty-one, or within three years of what is now the age for compulsory retirement. Still, his health and constitution were such that he was physically the equal of much younger men, and he was well fitted to start again on his military career, one which was destined to give him a prominent place among the successful generals of a great war.

The Sixtieth New York at that time was stationed near Baltimore, Md., where it had been ordered on duty as a railroad guard. Though composed of exceptionally good material, the regiment was lacking in discipline, its morale having been impaired by dissatisfaction arising from various causes. The former colonel had just resigned in response to a written request signed by all the line officers, thus creating the vacancy to which Greene had been appointed. His arrival in camp was a surprise to all, and a disappointment to some of the officers, who would have received a promotion in case the vacancy had been filled from within the regiment.

The new colonel called a meeting of the officers at his tent, where, in a brief address, kindly but firm in tone, he told them what he expected of them. Under his instruction the regiment made a speedy improvement in drill and discipline, and soon attained a degree of efficiency that in time made it a first-class fighting machine.

But Colonel Greene's service as a regimental commander was of short duration. After a stay of three months with the Sixtieth New York he received his promotion as a brigadier-general, his commission bearing date of April 28, 1862. He left the regiment with the good will and best wishes of officers and men. He was succeeded by Lieutenant-Colonel William B. Goodrich, a gallant soldier and courteous gentleman, who. was killed a few months later at the battle of Antietam while serving in Greene's division. (p. 66)

Greene received his commission as brigadier-general on May eighteenth, and his active service then began; it continued unbroken, except while disabled by wound, until the surrender of Johnston's army, nearly three years later. With his commission came an order to report to General Banks, then commanding the Fifth Army Corps, fighting up and down the Shenandoah Valley against Jackson. On May twentieth Greene said good-bye to his regiment at Relay House and arrived at Winchester that evening, reporting to Banks at Strasburg the next morning. It was a week before arrangements could be made to assign him to command; and in the meantime, on May twenty-fifth, Jackson attacked Banks with a greatly superior force at Front Royal and Winchester, and forced him to retreat to the Potomac at Williamsport. During these engagements and the retreat Greene remained with Banks' staff, and Banks, in his report, says that he "rendered me most valuable assistance."

Two days after reaching Williamsport, Greene was assigned to the command of the Third Brigade of the First Division, which had hitherto been commanded by his friend, George H. Gordon, Colonel of the Second Massachusetts Regiment; and Gordon left for Washington on leave of absence, Greene riding with him as far as Hagerstown.

The circumstances under which Greene took command of his brigade are briefly described in the volume, "Slocum and His Men; a History of the Twelfth and Twentieth Corps:"*

"After its retreat from Strasburg, Banks' corps remained on the north side of the Potomac, in the vicinity of Williamsport, until June tenth, a delay due in part to the heavy rains and swollen condition of the river. The men enjoyed a much-needed rest, and an opportunity was afforded to refit the column preparatory to resuming the campaign. While at Williamsport, a nice-looking, elderly gentleman in the uniform of a brigadier came to camp and presented

______

*"Slocum and His Men; a History of the Twelfth and Twentieth Array Corps." By Lieutenant-Colonel William F. Fox, U. S. V. (p. 67)

instructions from the War Department, placing him — General George S. Greene — in command of Gordon's brigade. He retained this command for a short time only, as Gordon was soon promoted brigadier for meritorious service in the preceding campaign, and on June twenty-fifth was restored to his position. But we shall hear a good deal more about this same General Greene before we are through with the records of the Twelfth Corps.

"The river having subsided, the corps recrossed, the regimental bands playing the then popular tune of 'Carry Me Back to Ole Virginny,' and moved southward by easy marches up the valley.

"The return to Winchester revived the bitter hatred with which the soldiers regarded the citizens on account of the treatment received from the people during the recent retreat through the streets of that town. The soldiers asserted that some of their comrades had been killed by shots fired from houses along the line of march. But they resented most the scandalous action of the Winchester dames, who from the upper windows hurled upon them objectionable articles of bedroom crockery. In two regiments of Greene's Brigade the men were outspoken in their threats to burn certain houses which they specially remembered.

"The wise old brigadier heard, but said nothing. Just before entering the town he issued orders that the troops should march through the streets in columns of fours, and that no officer or man should leave the ranks for any reason whatever. As they entered the place the two disaffected regiments found themselves flanked by other troops closely on each side, and they were marched through Winchester without a halt out into the fields beyond, feeling and looking more like a lot of captured prisoners than the gay, fighting fellows that they were. They cursed 'Old Greene' in muttered tones, but soon forgot it, guessed he was all right, and in time cheered the General as noisily as any other regiments in the brigade."

While Gordon was in Washington he was himself promoted to the rank of brigadier-general on June ninth, and, being very desirous (p. 68) to resume command of his old brigade, he procured a specific order from the War Department to that effect. In the meantime Jackson had retreated up the valley and Banks had followed him as far as Winchester, where the two armies were confronting each other, when Gordon arrived with his order on June twenty-fifth. The following day Greene turned over the command of his brigade to Gordon and started for Washington, stopping a few hours at Harper's Ferry to see his son Charles, a lad of twenty years, then serving as a private in the Twenty-second New York Regiment.

On June 26, 1862, the Army of Virginia was organized and General John Pope assigned to its command. It consisted of the troops on the Rappahannock under McDowell, those in the West Virginia mountains under Fremont, and those in the Shenandoah under Banks. The designation of the latter was changed from the Fifth Corps, Army of the Potomac, to the Second Corps, Army of Virginia. General C. C. Augur commanded its Second Division, and Greene was assigned to the command of the Third Brigade, then composed of the Sixtieth New York (his old regiment), Seventy-eighth New York, Third Delaware, Purnell (Maryland) Legion, and First District of Columbia, the last consisting of a small battalion only. Greene received his orders in Washington, July ninth, and took command of his brigade at Warrenton, Virginia, on July twelfth.

During the previous month Lee had brought Jackson from the valley to join him at Richmond in time to take a decisive part on June twenty-seventh at Gaines' Mill and in the succeeding "Seven Days' Battles." But no sooner had McClellan moved to the James than Lee began to plan his advance toward Maryland, and, as usual, the most important part in it was assigned to Jackson. On July thirteenth Lee ordered Jackson from Richmond to Gordonsville to meet Pope and hold him in check. Advancing north from Gordonsville, on August eighth, with his own and Ewell's and A. P. Hill's divisions, Jackson met Banks' corps, which formed the advance of Pope's army, on the following day, and (p. 69) an important battle was fought at Cedar Mountain on August ninth. Jackson outnumbered Banks two to one, but Banks did not hesitate to attack, and it was a sharply contested battle from about five o'clock in the afternoon until after dark. At one time Jackson's left flank was turned, and he narrowly escaped total defeat. If he had not been Jackson he probably would have been defeated. His own report, as Swinton says, uses "the words in which a general is apt to describe a serious defeat." But Jackson rallied his men by his own personal influence, and at dusk forced Banks back to the position from which he had moved to the attack. It was, in short, a drawn battle, followed by the retirement of Jackson to Gordonsville, and Banks to Culpeper. Jackson had lost 229 killed and 1,047 wounded, and Banks 302 killed and 1,320 wounded. As Banks had eighteen regiments* and about seven thousand men, and Jackson had forty-nine regiments* and about fifteen thousand men, the losses will indicate how gallant was the attack and the defense of Banks' Second Corps. Although not a decisive victory for either side, it brought Jackson to a standstill until Lee could rejoin him with his entire army a week later.**

In this battle Greene's Brigade held the extreme left, as later it held the extreme right at Gettysburg. The greater part of his brigade had been sent away a week before on detached service — the Sixtieth New York and Purnell Legion to Warrenton, the Third Delaware to Front Royal — leaving only the Seventy-eighth New York, the District of Columbia battalion and McGilvery's battery, Sixth Maine, a total force engaged of only 457 men. This handful of men was stationed on the extreme left, in front of Cedar Run, and extending to the woods at the base of Cedar Mountain. McGilvery's battery was in front of them and supported by them. The most persistent fighting was further to the right by the four

___________

*Official Records, Vol. XII, Part 2, pp. 138 and 179. Rickett's division of McDowell's corps arrived on the field shortly after seven o'clock in the evening with sixteen regiments; but the battle was then practically over, although this division lost 13 killed and 2-24 wounded.

**Considerable space is given to a general account of this battle because its size and importance have not usually been understood.

(p. 70) other brigades of the corps — Crawford's, Gordon's, Geary's and Prince's. But a determined effort was made by Ewell to crush the left flank. This movement was entrusted to Trimble's brigade, consisting of the Twelfth Georgia, Twenty-first North Carolina and Fifteenth Alabama, with Latimer's battery, numbering in all probably 1,200 men. Ewell's and Trimble's reports and the maps prepared by Trimble and Hotchkiss, all of which are published in the Official Records, tell the same story. Trimble was to make his way through the woods along the western side of Cedar Mountain, silence McGilvery's battery and drive in the Federal left flank, viz., Greene's Brigade. Trimble says that his battery was in position at three o'clock and continued firing until five o'clock, when his infantry advanced with the Alabama regiment as skirmishers to turn the enemy's flank, the other two regiments attacking in front. He further states that at dark, after seven o'clock, he "had possession of the ground occupied by the Federal left." In other words, during two hours, the hours of the heavier fighting to the west, he made no progress. Greene's Brigade and McGilvery's battery held their ground. The withdrawal across Cedar Run at dark was part of the general withdrawal of the entire corps by Banks' order. The losses in the two brigades were about the same, although Trimble had nearly three times as many men as Greene.

This was the first time that Greene had exercised command in battle. His part was by no means the most important on that day; he was simply to hold fast to a certain position and not be driven out, the holding of this position being essential to the progress of the fight. He performed this part completely, satisfactorily. He was to have the same duty, each time with more at stake, at Antietam, and again at Gettysburg; and each time he rose to the occasion. The essential feature of his career is the unflinching tenacity with which he held fast to a vital position, always in compliance with orders, and against enormously superior numbers. His services at Cedar Mountain received the hearty commendation of his superiors, Pope, Banks and Augur. General Augur, division commander, speaks (p. 71) of "Greene, who, with his little command, so persistently held the enemy in check on our left."

Augur and Geary were wounded during the afternoon, and Prince was captured in the darkness at the close of the engagement. The command of the division thus fell on Greene, and was retained until some time after Antietam. One week after the battle, August sixteenth, Lee joined Jackson with his whole army, and immediately began his advance northward. In this campaign Banks' corps took practically no part. Pope, in his report written at New York in January of the following year, takes occasion to criticise Banks, who, he says (at Cedar Mountain), "contrary to his suggestions and to my wishes, had left a strong position which he had taken up and had advanced at least a mile to assault the enemy." He further says that "Banks' corps, reduced to about 5,000 men,* was so cut up and worn down with fatigue that I did not consider it capable of rendering any efficient service for several days." The accuracy of this judgment may well be questioned, but Pope acted upon it, and, during the two weeks of incessant fighting and marching, in which Pope was driven back from Culpeper to Washington, no more important duty was assigned to Banks' corps than to guard the immense trains and endure the fatigue of endless marching and countermarching. On the fatal day of August twenty-ninth, during the fierce fighting at Manassas and Groveton, about which there has been so much controversy, Banks' corps was at Bristoe Station, barely seven miles from Groveton by a fairly good road which would have brought it squarely against Jackson's right flank.** It had been there for more than twenty-four hours. It could have reached Groveton in three hours at the most. Who would say that if Pope, instead of leaving Banks at Bristoe to guard the stores which on the following day he ordered him to burn up, had brought him up with 8,000 fresh troops to strike

________________

*Banks' monthly return for August gives the number "present for duty" 8,851. Official Records, Vol. XII, Part 3, page 780.

**Greene's pocket dairy contains this entry on August 29: "Firing north of us. Heavy cannonading." 71

(p. 72)Jackson's right flank during the afternoon of August twenty-ninth, the result would not have been different?

Greene's part in this discouraging retreat was simply to carry out his orders, guard the trains and care for the men in his division, three brigades and fourteen regiments, saving them as far as possible from unnecessary fatigue in their harassing duties and keeping them efficient for any emergency.

With the rest of the corps Greene arrived at Fort Albany, near the Long Bridge, at Washington, on September third. On the previous day the army of Virginia was merged into the Army of the Potomac under McClellan. Pope was relieved of his command and Banks was ordered to assume command of the defenses of Washington. His corps now became the Twelfth Corps of the Army of the Potomac — the third change of designation within five months. Major-General J. K. F. Mansfield was assigned to the command of the corps, and Williams and Greene commanded the two divisions.

At the battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862, Greene's division was not only actively engaged, but made a record for hard fighting, good generalship and effective service that has received favorable mention from every historian of that famous field. General Greene has become so well known by reason of his brilliant achievement at Gettysburg that there is a tendency to overlook or forget the good work accomplished by him and his division at Antietam. In order to explain the part which Greene's division took in the battle of Antietam, it is necessary to refer in the briefest possible manner to the general features of the battle.